On Aug. 7, Associate Editor at Sports Illustrated Kids and Hockaday alumna, Elizabeth McGarr McCue ’01, found herself talking back, rather angrily, to her living room television.

Just a couple of minutes earlier, she had switched channels to watch Olympic swimmer and 2012 gold medalist Dana Vollmer attempt to defend her title in the 100-meter butterfly at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics. McCue expected the race to be exciting. What she didn’t expect was NBC announcer Bob Costas commenting on Vollmer’s motherhood and post-pregnancy weight loss.

“For that announcer to call out the fact that a mom can’t be competitive, I was outraged. Of course a woman who had a child will still want to win a race and succeed in life,” McCue, who is a new mom herself, said.

Costas’ gendered remark was just one of many examples of sexist reporting that McCue was able to recall from the Summer Games in Rio. And she’s not alone. With the recent Olympics and current presidential race garnering a record amount of news coverage, people all around the world are noticing sexist journalism and speaking out about it.

Looking Back: a Double-Standard Media

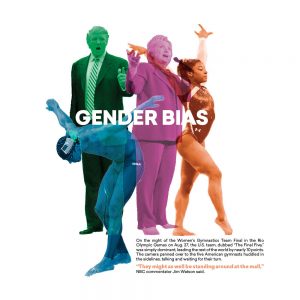

On the night of the Women’s Gymnastics Team Final in the Rio Olympic Games on Aug. 27, the U.S. team, dubbed “The Final Five,” was simply dominant, leading the rest of the world by nearly 10 points. The camera panned over to the five American gymnasts huddled in the sidelines, talking and waiting for their turn.

“They might as well be standing around at the mall,” NBC commentator Jim Watson said.

Critics were quick to point out the inherent gender bias underlying this comment.

“You wouldn’t be talking about male gymnasts like that,” a Twitter user posted.

“They could be standing in a mall”

…you wouldn’t be talking about male gymnasts like that. #TeamUSA #ArtisticGymnastics #Rio2016— Wicked Ginny (@GinnyLurcock) August 7, 2016

And this instance with the gymnastics team is just one of many deemed as gender-biased media coverage of the Olympics. Entire lists of such instances have been made, including The Huffington Post’s “Top 10 Most Sexist Things To Occur At The 2016 Rio Olympics So Far.”

When asked on her opinion of general sports coverage, Upper School Math Teacher and assistant swim coach Rachel Grabow’s mind jumped to the apparent double-standards of the media.

“I watched all of the swimming and running in the Olympics and some gymnastics,” Grabow said. “And this is something that other people have been commenting on as well: how the reporting differs for the genders.”

According to Grabow, gender-biased sports media stems primarily from people’s ingrained beliefs on the place of women in sports.

“I think part of it is our idea of masculinity versus femininity,” Grabow said. “We often think of men as being strong and participating in sports as more acceptable or commonplace in our society. But, [gender bias] is also more in the public awareness now than it was in the last Olympics, so I think gender equality has improved in sports already.”

Just a few weeks later, on Sept. 17, Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton stood inside her campaign plane, surrounded by a circle of microphones. Blue posters emblazoned with the words “Stronger Together” lined the cabin walls. Clinton was responding to questions from a flock of reporters about the midtown Manhattan explosions that had occurred earlier that day.

And several media outlets, including Bustle, responded to Clinton’s statement with news stories titled along the lines of “Hillary Clinton Looked Tired at 11:00 p.m. While Reassuring New Yorkers About the Explosion, and People are Freaking Out.” The hashtag “#ZombieHillary” even began to surface on Twitter.

Upper School history teacher Tracy Walder, who agrees that there is some degree of bias in media reporting, noticed the media’s more insistent investigations of Clinton’s health compared with Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump’s.

“I think the thing that upsets me the most recently is the whole medical records issue,” Walder said. “They’re talking more about Hillary’s health, but Donald’s actually older.”

Coverage of both the past Summer Olympics and the forthcoming presidential elections has been continuously stained by accusations of media coverage. This gender bias is a significant link between these two otherwise highly different events.

This bias is not new, but if anything, it has improved from years past. A 2003 study from the Journal of Communication found that men received twice as much NBC prime-time as women in the 2002 Winter Olympics. In contrast, a study featured in the book “Olympic Television: Inside the Biggest Show on Earth” revealed that 58.5 percent of prime-time coverage in the 2016 Summer Olympics was devoted to women.

The relationship between people and the media is a convoluted one: media outlets depend on people for viewership and support, and people depend on the media for reliable, desirable news. How does the media handle its responsibility of providing unbiased coverage? And how should the public receive and respond to slanted news when it inevitably comes?

Behind the Reporter’s Pen

With the exception of opinion pieces and editorials, journalistic objectivity embodies a significant principle in the media world. Journalists strive to maintain disinterest in order to give the public bias-free (and sexism-free) news. Garry Leavell, Assistant Managing Editor of the sports section at the Dallas Morning News, attests to this.

“From a professional journalistic point of view, our job is to root out any sexism in our coverage,” Leavell said. “We try to take a lot of care not just with what we write but what we cover to avoid that.”

However, a sexist headline or a slanted news story crops up from time to time. One widely criticized example from the Summer Olympics was the Chicago Tribune’s publishing of a story with the headline “Wife of a Bears’ lineman wins a bronze medal today in Rio Olympics.” This headline neglected to mention the medalist’s name, referencing her husband’s profession instead. (The headline has since been changed to “Corey Cogdell, wife of Bears lineman Mitch Unrein, wins bronze in Rio.”)

McCue attributes this Tribune’s headline to old habits of writing attention-grabbing—and often male-centric—headlines. “That person was taught to write headlines a certain way so they’ll get traffic on the Internet,” McCue said. “Their readers want to know about the Chicago Bears. It’s about what generates readers, and it’s what we are surrounded by and what pops into someone’s head.”

Associate Professor of American Studies Cheryl Cooky, Ph.D., teaches courses on gender and sexuality in sports and in the media at Purdue University. According to Cooky, it is difficult to determine the root cause of sexism in media coverage. Nevertheless, there are three main elements of U.S. sports that have contributed to bias: historically, sports are male-dominated, male-identified and male-controlled.

“Male-dominated means that the majority of those who play sports have been and are men. Male-identified refers to how our culture associates athleticism with masculinity,” Cooky said. “Male-controlled means those who are in power, decision-making positions are men.”

By “decision-making positions,” Cooky means that the majority of editors, journalists, broadcasters and sportswriters are men.

“This in part shapes the amount and type of coverage female athletes receive,” Cooky said. For McCue, a former Nascar reporter, the male-domination in the sport is palpable. “There’s certainly not a lot of female reporters in Nascar,” McCue said. “When you’re surrounded by men who aren’t used to seeing women all the time, you can feel intimidated. Sometimes older men can come off as patronizing. They certainly don’t mean to, but sometimes they aren’t used to explaining things to a 5-foot, 3-inches woman.”

Both Leavell and McCue acknowledge that in the newsroom, journalists do conscientiously aim to limit bias on females portrayed in the media. In the Dallas Morning News, Leavell noted that writers have an editing process where they first talk about stories beforehand.

“If we perceive there could be an issue, historically female gymnasts in particular, there’s always a heightened sensitivity as to how they are characterized, how they’re described, the adjectives you use to describe them,” Leavell said.

Accordingly, McCue cites awareness and care when writing stories as powerful tools to combat possible bias.

“Tell all sides of the story, do your research, think through the adjectives you use to describe somebody,” McCue said. “If you are reporting the story with all the facts, the only room for bias is if you’re leaving a part of the story out and using certain descriptions to suit your narrative.”

Reflecting on the media coverage of the Olympics last summer, Leavell acknowledges that while there were a few instances of sexist reporting, most journalists that he reads and knows strive greatly to be as fair as possible in their coverage and reporting. Indeed, he saw most of the Olympic coverage as fair and celebratory of female athletes.

“I would challenge the idea that there was a lot of [bias] in the overall media coverage of the Olympics in how much coverage there is of the Olympics,” Leavell said. “It’s an overwhelming amount, so those instances are certainly valid, but I don’t think that’s the majority of the coverage.”

According to Leavell, general sexism in the media has already improved greatly from 20 to 30 years ago, when women’s sports had an extremely low profile. He recalls that when he graduated from college in 1989, the Women’s Final Four basketball championship had only existed for about five years. A U.S. women’s soccer team had not yet taken shape. The Women’s National Basketball Association had not yet been created.

“[Women] are now a regular part of the sports landscape,” Leavell said. “Do they get the same amount of media attention that the most popular male sports get? No, for sure, they still don’t. But I would like to think and hope that our country is more enlightened on women’s issues than 30 years ago.”

How Do We Respond?

Scientific studies, such as those performed by the National Technology for Biotechnology Information, show that sexism has a longstanding negative effect on women’s mental health. Reading degrading or biased headlines can lead to stress, depression and low self-esteem. However, some people note that the growing list of sexist interviews, headlines and articles actually creates both beneficial and adverse effects in the classroom and on the field.

In a survey sent out to the Hockaday Upper School, several students said that they change certain aspects about themselves because of sexist reporting. “After reading some of these stories, it makes me feel very conscious about how I act and speak and like I have to fit a very specific mold,” an anonymous student said in the survey.

Hockaday’s Head of Athletics Tina Slinker, who before coming to Hockaday was the women’s basketball coach at the University of North Texas, categorized girls who consume sexist media in three ways: those who are fearful of what they hear, those who are motivated to do better and those who want to commit themselves to changing the world of reporting by choosing journalism as a career path.

Slinker also admits that she holds her athletes to a higher standard because of how the media treats women in sports. “When I prepped my [college] athletes for an interview, I always made sure they were dressed properly and knew what they were saying,” she said. “Any slip-up can be misunderstood by the media and ruin your reputation.”

Beyond the latent silver lining that some people have managed to find, the negative effects of sexist reporting can take a toll on girls. Supporting Slinker’s argument, junior Shelby Schultz, who plays varsity basketball and is an avid sports fan, said that sexism alters her personal outlook on life.

“It not only affects my self-image and makes me feel that my effort in sports is for naught, but also creates an environment in which women have to prove themselves as athletes and sports fans,” Schultz said.

In turn, a majority of Upper School girls surveyed—about 78 percent—respond to such instances of sexist reporting by telling their friends and families about it. Schultz believes that opening up conversation about sexist reporting will prove beneficial in the long run.

“Conversation is the first step in changing the system,” Schultz said. “If people in our generation can identify and talk about the issue in their households, they will be more bold in working to resolve it.”

Looking Forward: Platforms for Change

Ultimately, the public’s calling out of sexist comments provides an opposing force to inherent journalistic bias. Leavell saw the public pushback against the “Wife of Chicago Bears” headline in a positive light.

“It’s the ultimate goal to eliminate bias within your coverage,” Leavell said. “Calling out and criticising that bias heightens the sensitivity for people.”

One solution forward, cited by both Leavell and McCue, is the diversification of the newsroom—especially with more females in editorial positions. “I’m sure any sports editor would tell you that they wish they had more diversity among their staff,” Leavell said. “And probably a lot of employers would tell you the same thing.”

These journalists strive to diversify not only the personnel, but the content of stories written. McCue actively tries to raise awareness on the accomplishments of female athletes in Sports Illustrated. “We definitely try to include female athletes and their backstories in Sports Illustrated Kids because that’s an important way to influence the next generation,” McCue said. “For them to see powerful women succeed and how they got here today—we try to be very inclusive at Sports Illustrated Kids for that reason.”

In addition to these internal fixes for the journalism industry, social media has proven to be a valuable impetus for promoting change. Leavell calls social media “a game-changer,” particularly as a forum for dissemination and debate. Accordingly, 38 percent of Upper School students surveyed first learn about sexist commentary from other people posting about it on social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram.

While she admits social media and public criticism can draw attention to sexist reporting and thus effect change, McCue also warns people to avoid excessive ire towards the media. “Are we shaming or bullying the reporter who did this?” McCue said. “I think the goal should be to be thoughtful and provocative in our questions and ask, ‘Why did this happen?’”

Overall, many journalists, students and teachers alike believe that solving bias comes down to education. Organizations have been echoing this sentiment by educating the next generation of reporters on how to cover women and men equally.

MediaShift, a media and technology analysis company, recently published an article on their website with advice on how journalism educators should teach their students unbiased reporting. The company acknowledges that many headlines out of the Olympics and the presidential election were sexist because reporters were used to men in sports and politics. When faced with a high concentration of women athletes and an unprecedented female presidential nominee, current reporters are unprepared to cover these situations. MediaShifts tells teachers to emphasize being informed, employing the old adage, “think before you speak.”

In addition, Columbia Journalism Review, which is published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, publishes articles on fair reporting such as “How to Report on Hillary Clinton.”

At the end of day, the process for reform for a fairer media will be a gradual, perhaps painful one associated with a long-term cultural shift. Schultz understands this and believes that as exposure increases for successful women, more people will acknowledge them and support their future endeavors.

“The more we recognize sexist media and support those who publicize women’s achievements, the sooner we will reach a point where women in the media are defined by their achievements,” Schultz said. “Then, we will reach a point where young women will look to the media and find encouragement that they will succeed.”

– Shreya Gunukula, Video Editor – Elizabeth Guo, Copy Editor –