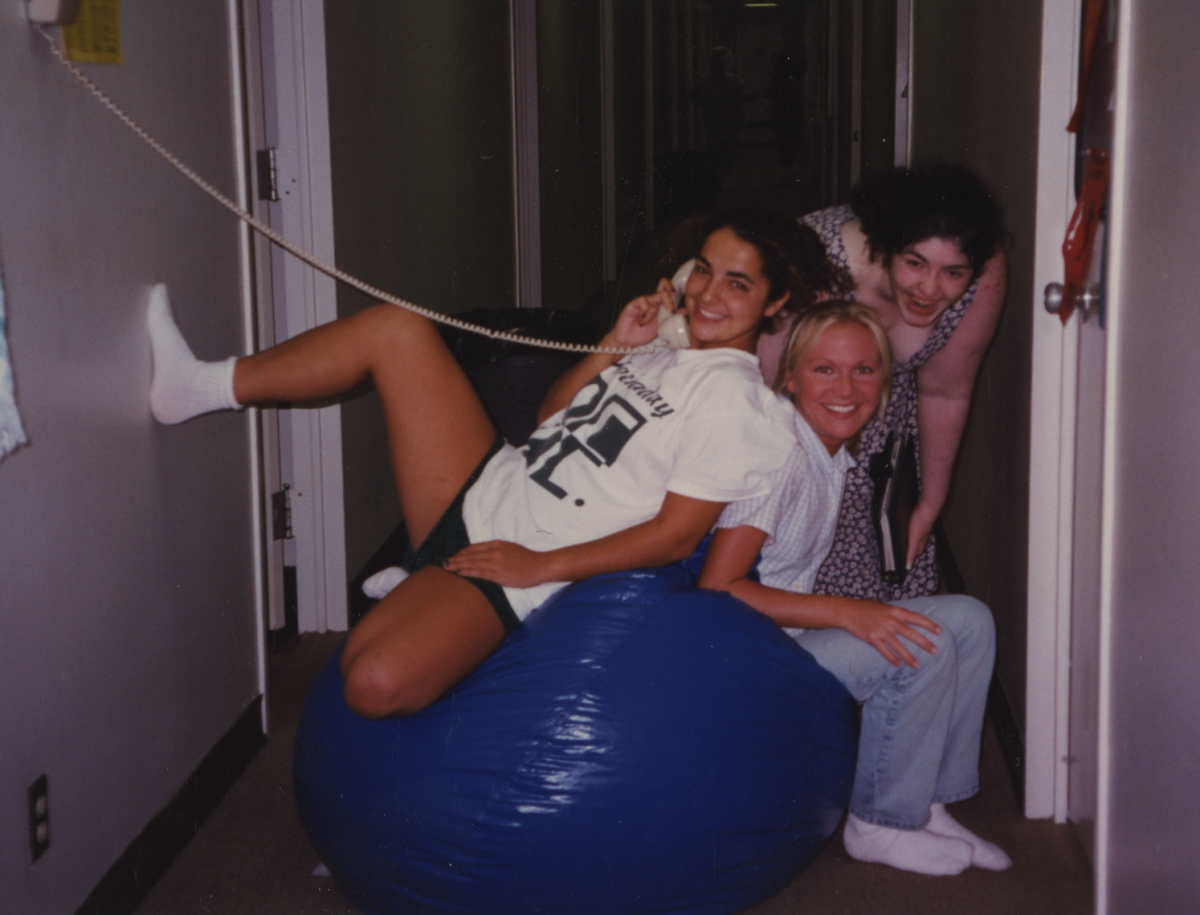

$1.50 – Asian male. $1- Caucasian. Free – Native American.

These were the prices of goods at an anti-affirmative action bake sale at the University of Texas on Oct. 26 that attracted over 100 student protesters.

Organized by a student group, Young Conservatives of Texas, this bake sale protesting affirmative action priced their goods in correspondence to which ethnicities are most affected by affirmative action. The prices of the confections descended from Asian to white to African to Hispanic to Native American.

But, according to YCT-UT chairman Vidal Castañeda, there was a reason for the bake sale.

“Our protest was designed to highlight the insanity of assigning our lives value based on our race and ethnicity, rather than our talents, work ethic and intelligence,” he posted on the group’s Facebook page that day.

In Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978, the Supreme Court prohibited the use of racial quotas in the college admissions process. However, the justices contended that colleges could consider race as one factor in admissions.

Affirmative action, a policy favoring underrepresented groups in the corporate and educational systems, has been long debated since its initiation 48 years ago during the civil rights movement. In its tumultuous history, the policy has been praised for redressing discrimination against minorities and criticized for administering an unfair advantage for them.

The definition of diversity has broadened in recent years from just race and ethnicity to socioeconomic status, gender, sexuality and more. The Common Application, the most widely used application system in the U.S., allows applicants to fill out an ethnicity with which they identify.

This information is stored in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, a system of surveys conducted by the National Center for Education, in which colleges’ demographics can be monitored. According to Forbes.com, some university boards require the university to have a certain demographic ratio. As a result of the diversity ratio some universities are seeking to fill, high school students feel pressured to claim ethnicities to reap the benefits of affirmative action, even if they don’t identify with that ethnicity.

Race Behind the Admissions Curtain

According to Dr. Jedidah Isler, an astrophysicist and the first African-American woman to receive a master’s degree in physics from Yale University in 2014, race and intellect are completely unrelated. In her article, “The Benefits of Black Physics Students,” a reaction to ex-Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia’s qualms about ability of black students to succeed in higher-paced institutions, she addresses the need for affirmative action to afford equal opportunity to minorities.

Senior Addie Walker shares a similar view. Acknowledging that there are faults in the system, Walker said that the original intent of affirmative action is still needed today. “There are minority groups that tend to score lower on those tests and aren’t given the same opportunities. It’s there to level the playing field,” Walker said.

Statistically, races that benefit from affirmative action tend to be more disadvantaged in terms of socioeconomic status and accessible opportunity. Household income often varies by race. In 2015, the Census Bureau estimated that Asian-Americans have the highest average annual income at over $74,000 and African-Americans have the lowest at $35,000.

This information directly correlates to educational opportunities provided to students of disadvantaged races. A National Center for Education Statistics census shows that in 2015, the average SAT math score for black, Hispanic and Native American students was 400-450 out of 800, compared to an average score of 600-650 for Caucasians and Asians.

In response to the statistic, colleges use the Federal Pell Grant Program to diversify their undergraduate class. This program established by the U.S. Department of Education “provides need-based grants to low-income undergraduate … students to promote access to postsecondary education.”

Not all universities are fixated on their ethnic demographics. For example, California’s Proposition 209, passed 20 years ago, prohibits the University of California schools from admitting students based on race. The UC system is legally bound to eliminate diversity quotas, while private institutions are at liberty to establish quotas in their admissions processes.

Director of College Counseling Courtney Skerritt believes that the diversity requirement is no longer solely about race and ethnicity.

“In the past five years, it’s become less of a conversation about ethnicity and more about socioeconomic backgrounds. A trend that I have seen in the past 10 years is that applicant pools are getting more diverse in every way, geographically and in terms of gender and sexual identity,” Skerritt said.

In her years of experience as a college counselor, Skerritt has noticed that race and ethnicity do not play as significant as a role in the admissions process as students often think.

“My experience shows that if you are admissible to an institution, then you are admissible to that institution, whatever color your skin may be,” Skerritt said. “Yes, colleges take race into account, but not as much as perceived to be.”

The Student’s Take

The college admissions process is said to be a holistic one, in which all applicants are considered based on their entire application, not just their GPA, test scores, personal essays or the race they check on the application. This practice supposedly enables the college to take into account a student as a whole person, rather than numbers and statistics on an application.

A holistic review introduces subjectivity to a decision, making it difficult for colleges to explain who gets in and why. Sara Harberson, former Associate Dean of Admissions at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in the Los Angeles Times that, to some degree, the holistic system has become a cover for cultural and racial biases that are precepts in the admissions process, calling for a change in the system itself.

Senior Cat Colson also believes that a larger-scale systemic change is needed.

“I think that it is more of a flaw with the system itself, as opposed to people who are putting ethnicities that they don’t identify with,” Colson said. “You can’t expect everyone to be straight-up honest.”

Conversely, senior and Student Diversity Board Chair Sahar Massoudian finds fault with both the system and students who are not completely honest about their ethnicities. While Massoudian recognizes that this dishonesty does not stem from a place of malicious intent, she regrets the lack of awareness associated with it.

“[People falsely claiming identities] disappoints me because that is obviously cultural appropriation, you’re taking somebody’s ethnicity and you’re saying that you have lived through the same experiences that a person of this ethnicity has lived through,” Massoudian said.

Massoudian concurs that if students feel pressured to appropriate another culture, then there must be a defect in the system.

“The part that makes me saddest is that I think the reason people do it is because they believe one ethnicity one-ups another in terms of college admission, and they don’t realize that every type of cultural background, ethnicity and experience you have is unique. You’re always going to be bringing something different to the table,” Massoudian said.

Racial and ethnic ambiguity also presents a complication in the affirmative action system. Many people identify as one or more ethnicity or race, which makes it difficult for them to choose one to report to colleges.

Junior Anden Suárez is both half-Mexican and half-German. Identifying more with the Mexican side of her lineage, Suárez plans to pick Hispanic on her college application.

“With affirmative action, it definitely will give me an upper hand in terms of the quotas that colleges have to fill, but I have no qualms about using that because it’s true, and I’m not going to check non-Hispanic because I’m half Mexican,” Suárez said.

That being said, Suárez acknowledges that affirmative action exists for other purposes, as well.

“There are a lot of Hispanics that deserve more of an extra chance or more of a boost from affirmative action than I do because freckled skin and green eyes give me a lot of privilege,” she said.

Nationwide Affirmative Action Debate

Though the Supreme Court upheld the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment permitting consideration of race in undergraduate admissions decisions under strict judicial standards in Fisher v. UT, there is still a discussion about the role of affirmative action and diversity ratios in the college admissions process.

In November 2014, Students for Fair Admissions and, in May 2015, the Asian American Coalition for Education filed a complaint against Harvard University citing that it violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of color, race and national origins in activities and programs receiving federal financial assistance. The lawsuit alleged that Harvard University was discriminating against college applicants on the basis of race, specifically those who are Asian-Americans.

However, the National Asian American Survey reported that 69.1 percent of Asian American/Pacific Islander Americans of California registered voters were in favor of affirmative action programs.

Columnist for The Wall Street Journal Online Jeff Yang, an Asian-American and a graduate of Harvard University, said that this lawsuit is “just the latest attempt to derail an apparatus that has given hundreds of thousands of blacks, Hispanics and, yes, Asians a means to climb out of circumstances defined by our society’s historical racism” in a CNN opinion article.

Since Proposition 209 passed in 1996, “the minority student admissions at UC Berkeley fell 61 percent, and minority admissions at UCLA fell 36 percent” according to National Conference of State Legislatures. Additionally, there were 46 percent fewer African-Americans and 22 percent fewer Hispanic students in the undergraduate freshmen class at Rice University after Texas abolished its affirmative action program in 1996.

In concordance with Yang, Walker supports affirmative action when it is used to level the playing field in college admissions. However, she believes that people who check on applications an ethnicity or race that they don’t necessarily identify with are furthering inequality and undermining the purpose of affirmative action.

“I don’t think you have the right to use [ethnicity, race or culture] to advance you in your journey to college, because it takes away the purpose of having those things in the first place, which is to increase the diversity of an institution and the equity of an establishment,” Walker said.

Instead of focusing simply on the skin color and the ethnic background of a college applicant, Walker thinks that college admissions should look at the opportunities afforded to the applicants and take what they did with those opportunities into account.

“I think that the purpose of affirmative action is trying to help the people that can have the same amount or more potential but are in a position that they can’t fully express that potential,” Walker said.

Fellow senior Nicole Klein, who checked both Hispanic and Caucasian on her college applications, agrees with Walker that a student shouldn’t claim a race or ethnicity as their own on a college application if it hasn’t played a role in their life.

“Colleges should make it clear that being a certain race will not make or break your admission,” Klein said.

In regards to the affirmative action bake sale, UT Vice President for Diversity and Community Engagement Gregory Vincent, Ph.D, issued a statement describing the bake sale as “inflammatory and demeaning.”

As students apply for undergraduate college admissions this year, they must decide what box to check for their ethnicity and race. Skerritt said, “If a student asks me whether or not to check the box, I always tell them ‘if it’s part of your story.’”

The Fourcast reached out to multiple college admissions officers and students for this article, but they refused our requests for interviews.

Neha Dronamraju – Asst. A&E Editor

Maria Harrison – Asst. Features Editor