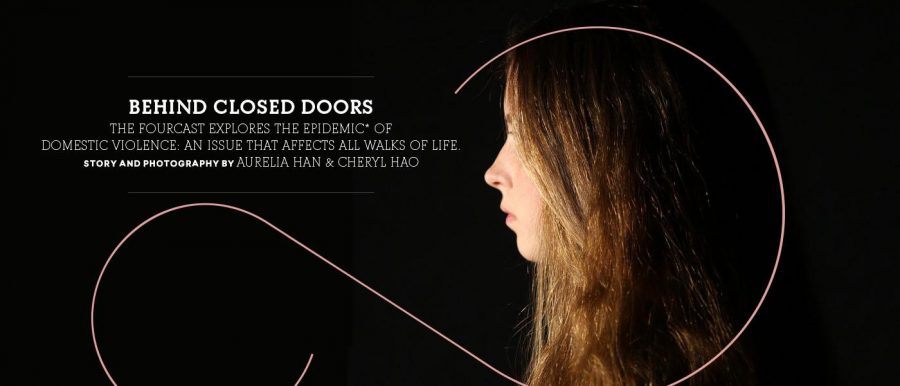

She is your locker neighbor. She is the girl in front of you in the lunch line. She is the faculty member who you always greet in the hallway. She could be you. Or perhaps, she is you.

One in three women in Texas will experience domestic violence in their lifetime.

Out of the 495 students in the Hockaday Upper School, 165 could be or currently are victims. That’s more than the entire senior class.

Domestic violence does not discriminate. Victims come from every race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education background, sexuality and age.

In a survey of 200 Upper School students and faculty or staff, 64 percent responded that they have known someone who has been a victim of any form of domestic violence. Fourteen percent of responders said that they themselves were or are victims of domestic violence.

This type of violence, according to Genesis Women’s Shelter in Dallas, occurs when a person in a relationship intentionally tries to establish power and control over the other through physical, psychological, emotional or sexual abuse. People often hear “domestic violence” and can tag the words rape or punching, and while these actions indeed make up a life-threatening part of the abuse possibilities, they only cover a fraction of the reality.

The blurred boundaries of domestic violence may partly originate from society’s tendency to romanticize actions or words, which belittles the victim and feeds power to the abuser. Today’s culture oftentimes romanticizes a boyfriend’s jealousy and possessiveness as a sign of true love, it paints the picture that passionate romance must include dominance and a dark-haired, dark-eyed gruff man who controls the girlfriend. On popular fanfiction website Wattpad, the titles of some trending stories include “Claimed by Him with Love,” “Endless Bonds” and “My Possessive CEO.” The latter has 14.2 million views and nearly 300,000 likes.

According to Jordan Watson, the Assistant Director of Clinical and Professional Services at Genesis, society thus justifies domestic abusive behaviors.

“I tell the story about going to watch ‘Twilight’ for the first time and just really being appalled by the movie because the idea is that this big strong guy loved [the female protagonist] so much and needed to protect her because she was so fragile and weak,” Watson said. “The message is that if a relationship is not dramatic, and we don’t have these big fights, so we can have big makeups, then it’s not really love.”

However, those big fights come with consequences, whether physical, sexual or emotional.

Partially due to the advertisement of these fantasy stories to teens and young adults and the lack of education in dating, 16 to 24-year-olds are the most likely to experience abuse, and often experience abuse at its highest in severity and danger. Forty-three percent of college women in the dating stages of their relationship encounter violent or abusive behaviors, and one in three girls will suffer physical abuse before the age of 17.

Then, as these young adults are beginning to enter more serious relationships, they are oblivious to harmful partners, and are thereby deceived into believing an abusive relationship is normal.

With less independence and sometimes lack of financial resources, this age group is more vulnerable to somebody coming in, dominating and making one feel afraid. In oppressive relationships, Hockaday’s Upper School Counselor Judy Ware worries that girls cannot determine when to draw the line, especially when it comes to their first loves.

“I worry about my girls here at Hockaday who are in abusive relationships with guys,” Ware said. “As young women and girls, we’re taught to be nice, to be peacemakers, to be loving and to be kind, and sometimes that doesn’t serve us very well.”

Another fallacy lies within the stereotype that domestic violence only occurs in low-income and uneducated homes and in disadvantaged communities. On the contrary, this abuse affects all neighborhoods and all families, no matter the background.

Sara Held, Hockaday senior and member of the Genesis auxiliary group Teenage Communication Theatre, learned many truths about domestic violence, amongst other societal issues, by listening to speakers during the summer and performing skits to schools around the community.

“We might hear about abuse in lower-income and uneducated situations a lot because that’s the way media portrays it,” Held said. “In reality, it happens so much more frequently than what we think within higher income families and between different types of relationships.”

While domestic violence can occur with the male as the victim, women are overwhelmingly the more common victims, as 89 percent of patients who report to emergency rooms on domestic violence calls are women. Held believes society upholds men in such a way that they are given a privilege of resources and benefits to escape abusive relationships unavailable to women.

Highlighting the difference between the ability to protect oneself and to leave an abusive relationship, Watson understands that in a situation where a man is dominating a woman, she in some ways becomes stuck because he controls all of her resources, money, support system and often the kids. In the classic “he said, she said” story, when it comes to domestic violence, the girl often loses because abusers tend to be charming and charismatic, making it inconceivable that he could ever lay a finger on her.

“Abusers often really care about their public image and put a lot of effort in looking good in the community, so it’s why abusers are men of positions, they are pastors, preachers, city officials and big business men,” Watson said. “They are the guy in the neighborhood that’s always grilling and playing with the kids.”

Anatomically, men are also oftentimes built stronger, giving them the upper hand physically and in some cases, a more feared presence.

This ability to trigger fear, anxiety and uncomfortableness defines domestic abuse, because once someone feels afraid or uneasy, she tends to change in that moment to protect herself. Although a lot of behaviors in relationships aren’t healthy and appropriate, like calling a sister a derogatory name, it’s not abuse if it doesn’t provoke fear. With the human natural instinct to change one’s behavior to stay safe, domestic abuse ultimately breaks down to power and control over another human.

The Physical Trauma

Physical abuse comprises two different types from the abuser: one is meant to hurt the victim and the other is to intimidate. The latter includes anything where the abuser uses his hands or body on the victim, which includes kicking, punching, slapping and strangling, a more common action in the recent years. On the other hand, physical abuse through intimidation, the abuser will never physically touch the victim but still uses his body to create a sense of fear by doing things like blocking the door in a room, punching the wall or knocking over a lamp.

As a result, a victim doesn’t have to show bruises or scars to have suffered from physical abuse. Even with bruises, to Meitra Doty, Ph.D., a psychiatrist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, the ability to conceal and cover with makeup and turtlenecks causes more challenges for one’s surroundings to recognize signs of abuse.

“With physical abuse, [the abuser] usually knows better than to hit you in the face or somewhere you can see or unable to cover up,” Doty said. “I’ve never had a woman walk in my office where I could see the bruises on her. It’s never that obvious. It’s always a lot more subtle.”

This is physical abuse.

Most people at Hockaday know Academic Technology Specialist Candace Townsley as the cheerful, curly-haired woman who signs off her emails with okie dokie! and hosts coding games for the Upper School students. Townsley is a wife, mother to 29-year old twins, friend and mentor in the Hockaday community, but these roles are a part of her survival story. Townsley is a domestic violence survivor. Previously in a physically and emotionally abusive relationship with her first husband, the father of her children, she lived in subjugation for one and half to two years (Read her story on p 18).

“I learned very quickly that he was a lot stronger than I was, and I learned very quickly, just like an animal will learn when you ding a bell and give him a treat that if I didn’t fight back, the beatings would stop more quickly,” Townsley said. “I tolerated the beatings for a while, but it wasn’t until he hit my eight-month-old twin children, my girls, that I knew I had to get out.”

She could defend herself, but her daughters were just babies, crying and not knowing left from right. It was her innate instinct, as a mother, to take care of her children and save herself and her daughters from this relationship.

No Consent, No Choice

During any instance and under any circumstances where consent was not given, the line crosses into sexual abuse. Characterized by any sexual contact without permission, rape consists of, but is not limited to, kissing, grabbing, sending nude pictures and forcing to engage in physical behavior. However, abusers also exploit coercive sexual abuse to avoid receiving consent by threatening and taking away the ability to say no.

“By threatening and saying ‘you are going to have sex with me, or I’m going to hurt you,’ the victim is not not choosing to have sex, she is choosing to protect herself in that moment,” Watson said.

The choice, consent and control are all taken away.

Over the past summer in a work environment, a Hockaday student, who will go by the alias of Isabella*, experienced sexual assault in the form of rape after explicitly saying no. Although Isabella and her abuser were not in romantic relationship, many times, abuse can be present in any type of relationships—not necessarily a romantic one. (Read Isabella’s story on page 18).

“I think I blamed myself at first, but one of my good friends said to me, “you said no, and he continued,” Isabella said. “It doesn’t matter if you kissed him 100 times before, if you say no, you stop.”

This is sexual abuse.

The Hidden Scars

Emotional and verbal abuse are often disregarded over physical and sexual abuse. However, it’s the most common abuse that occurs and includes actions like inducing guilt, intimidation, manipulating or lying, demeaning and being possessive, all of which causes a sense of fear from the victim.

Those who experience emotional violence often have trouble identifying and naming it as what it is: abuse.

An Upper School student, who agreed to speak under the name Carolyn*, struggled with this issue with her ex-boyfriend.

Carolyn did not realize she was in an emotionally abusive relationship until she had been engulfed in it for six months. When she told two of her friends on how he acted, they explained to her that she was being abused.

According to her, emotional abuse is not identified as a legitimate genre of abuse, and brushed off and blamed on the abuser’s crass personality, or from them simply having a bad day.

An Upper School Student, who spoke under the alias of Rebecca*, experiences emotional manipulation from her mother, and has only recently recognized the ongoing abuse that has plagued her life for many years.

“I never understood that [the abuse] wasn’t normal. I felt incredibly guilty to be thinking that this was abuse, when I knew that women were experiencing sexual abuse and physical abuse, which has never happened to me. I felt guilty to call this abuse,” Rebecca said. “I had always assumed that domestic abuse was violent or that the emotional aspects were inferior types of abuse, but really that’s wrong. They’re all equally harmful.”

The repercussions of emotional abuse hurt and affect their victims just as much as a broken bone or cracked ribs would.

With constant false reminders from their abusers such as “If you’re not with me, you don’t have anything,” “Nobody else loves you,” or “This is for your own good,” mentally healthy, strong and independent women are torn down into vulnerable, subordinate figures with no say in their choices.

This is emotional violence.

The Aftermath

Living under the hand of the oppressor takes a heavy toll on its victims.

The effect of all forms of domestic violence can result in diagnosed illnesses, most commonly post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression.

However, legitimate consequences do not always mean having a mental illness that’s professionally diagnosed. On a daily basis, victims and survivors may suffer from insomnia, nightmares and a heightened sense of paranoia, amongst feelings of uneasiness and high-alertness. Over time, these constant emotions result in distrust for future friends, family and, especially, partners.

If domestic violence victims survive their situation, they come out a different person as they were before. Their previous emotional or physical beatings often impose eternal shame and guilt. Some women blame their negative experiences on themselves, so survivors still feel like they could’ve prevented what happened; many women try and find every excuse to pin something on themselves.

Doty sees patients that are, or once were, victims of domestic abuse.

“As victims get beat down emotionally and psychologically, they start to think they deserve this—somehow they’re the bad guy—which makes it lot easier for them to become a victim of the domestic violence,” Doty said. “At that point, if they don’t have much self worth, and somebody puts their hands on them, they may not react the same way they would have a few years prior, if somebody just out of nowhere on their first date hit them.”

Especially if the victim has a history with the abuser, it may be harder to leave as the relationship progresses. According to Doty, between young couples, who usually live with their parents and are financially supported by them, there is an attachment to their first love.

There is an idea between the “firsts”: her first romantic partner, her first love, her first kiss and the first person she had sex with. This results in an impermeable emotional connection, even when the threat or prevalence of domestic violence is present.

As for partners who are married or are dependent on each other, she may have to consider that her partner may be her primary source of money and shelter before she even thinks about leaving. There also may be children in the picture, which prevents a woman from leaving the household and relationship.

“Both partners need to make decisions in a dating relationship. Not wishful thinking, like ‘this could be so wonderful,’ but ‘what have I seen so far?’” Ware said.

This shame and guilt that victims tend to experience are directly correlated to the low number of victims that share their stories with another person. The U.S. Department of Justice reports that approximately 25 percent of all physical assaults and 20 percent of all rapes are reported to the police. Even less incidents of emotional abuse are brought to the authorities. The U.S. Department of Justice believes that victims do not see the legal system as an appropriate tool to solve these disputes.

“There’s a stigma that this only happens to certain types of women, and it would be very humiliating to come out and say that this man was [abusing] me, and I let that happen,” Doty said.

And even after setting all stigmas aside and enduring the inner turmoil of debating whether to tell, victims still may experience shaming.

Isabella recalled that when her situation was made known throughout her workplace, there was a clear division in the reactions of her polarized co-workers. Her friends doubted her story and even blamed her for putting herself in that situation.

“People were saying, ‘Oh, you led him onto it,’ ‘You shouldn’t have hung out with him,’ and ‘It’s your fault.’ I never realized how prevalent that idea is,” Isabella said. “When I told my friends, their first question was ‘I’m sorry, are you ok? But the second question was, ‘how did you act?’”

How to Help

Given the statistics that one in three women is a victim of domestic violence, chances are that either you will be (or currently are) the victim, know someone who is, or both.

Looking in from the outside, especially if you are not close to the victim, there are not really any obvious signs and you cannot pick out the sufferer from a crowd of people.

“Victims are extremely good at hiding what they are going through. There are all kinds of sad faces in every hallway, but it can be about a million different things,” Ware said.

A Hockaday faculty member, who will go by the name of Nancy*, was the help and support system for her college roommate who was in a physically and emotionally abusive relationship. Nancy did not suspect that her roommate, a college athlete whose personality radiated confidence and strength, had been beaten by her boyfriend when she got home and stumbled.

“Something that hurt me through all of that was watching people make judgments and assumptions of others. None of us know what we would do until we’re in that situation,” Nancy said, “You don’t know. If you judge by an appearance, you’re never going to understand it because it just happens.”

If you think you are in an abusive relationship, assess your situation and know your resources: the school counselor, a trusted adult or friend and know that the local women’s shelter is open to anyone in need. If you believe your friend is in an abusive relationship, consider what your friend is going through, and that it is easier said than done. Give them time, but if you see no change, do not be the one to let the violence escalate. Remember that even though it may not seem this severe, in many cases, domestic violence escalates and it can be a life or death situation.

The support system is critical for domestic violence victims, but taking care of yourself comes first.

“You have to be your own advocate,” Townsley said. “You don’t want someone who finds joy in cutting you down and belittling you. You are worth so much more.”

In the time to be afraid, be brave.

If you are in a situation and need assistance, call the domestic violence 24/7 help-line: 1-800-799-7233

Aurelia Han – A&E Editor

Cheryl Hao – Assistant Web Editor