Ten years after the end of the Vietnam War, Thomas Hoang’s family only had enough money to send one of its children on a small fishing boat headed for the United States. As the oldest child at 24, Hoang boarded the boat in search of a land of more opportunity and said goodbye to his family, whom he would not see for another 12 years. Halfway into the long and arduous journey, the motor of the fishing boat died, leaving the boat stranded in the middle of the ocean. The hundreds of passengers on board panicked. They had no food and were completely lost, thousands of miles from land on all sides.

A U.S. boat sailed across the horizon and provided a glimmer of hope, and the remaining survivors screamed for help. The people on the boat, likely aware of the desperate pleas, ignored them and steamed on. Hockaday senior Lauren Hoang, the daughter of Thomas Hoang, recalled coolly that “the U.S. boats wouldn’t take them because the Vietnam War was not considered very popular at the time, so they didn’t want to take any more refugees.” Luckily, a Dutch ship picked up the remaining 26 refugees of the initial 200, including Thomas Hoang, and transported them to the Philippines, where they remained in refugees camps until the United Nations could resettle them.

Almost a half-century later, refugees still risk their lives in hopes of a brighter future. Refugees from across Southeast Asia and the Middle East pile into overcrowded, dilapidated dinghies in Turkey and cross the 4.1 miles to the small Greek island of Lesbos, the epicenter of the refugee crisis and the entrance into the European Union for many fleeing the region.

Abdullah Shawky, the Disaster Response Coordinator for Islamic Relief USA in the Dallas office, arrived on the island in October of 2016 to help the Greek Coast Guard assist the ships that reached the coast and to work in the U.N. refugee camp, which was hastily assembled in the parking lot of a popular Lesbos nightclub, Oxy. On his first day, he encountered a thousand refugees heading towards the shores, to whom he would shout out in Arabic that they would be safe and that they would not be arrested. Each day the numbers of refugees got progressively higher as refugees feared an eminent European Union action to restrict further movement.

During one particularly tumultuous night, Shawky observed the coast guard bringing in a sinking ship. However, while the coast guard normally docked on the far side of the harbor, on this occasion it docked on the closer side.

“I thought was it strange but then I realized the situation was so critical,” Shawky said.

After hearing reports that a baby on board was in critical condition, Shawky jumped onto the dinghy and shouted, “Where’s the baby? Where’s the baby? Where’s the baby?” Immediately, someone handed him the orange-tinted baby, whose color likely resulted from jaundice, and Shawky almost tossed him to the doctors to immediately start CPR. With the baby in the hands of physicians, Shawky and his friend, Akhmed, began providing first aid and striking him on the back to get the water out of his lungs.

“He eventually started to come to, and then we got him off the boat and that when I saw the baby again,” Shawky said. “He looked really blue, and he didn’t look good.”

Because Lesbos is small island and does not have many resources, it took the ambulance 30 minutes to arrive and pick up the baby and would likely take another 30 minutes to arrive at the hospital.

“We get word a little later that the baby was basically dead on arrival. For us that was very tough because it was the first death we had witnessed. We had heard about some deaths occurring at sea and bodies being picked up, but that was the first time we witnessed an actual death, especially of someone so young,” Shawky said.

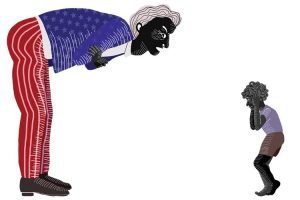

But the refugee crisis is no novel development in our modern world; for centuries, internal and external displacement have both compelled millions from their homelands, forcing them to risk their lives on dangerous voyages all in the hope of a better future in a strange new country. However, according to the U.N. High Commission on Refugees, the world has never experienced such high volumes of refugees, which surpassed the 60 million mark in 2015. In response to the growing crisis, a climate of xenophobia has surged, leading President Donald Trump to take swift action in curbing the number of refugees through executive order.

The Flickering Light at the End of the Tunnel

Every Wednesday at 12:30 p.m., Hatim Mohammed, a Sudanese refugee, attends Vickery Meadow Learning Center’s intermediate level English as a Second Language class in North Dallas. Mohammed, dressed in a vibrant purple-striped shirt and khaki pants, sits in a small classroom with 12 other students from around the world and struggles to pronounce the sound “er.” Despite his repeated attempts, Mohammed never ceases to smile, laughing off each mistake and then earnestly trying again.

While the journey to America is arguably the most challenging aspect of the refugee experience, those who finally make it still face tremendous obstacles. Like Mohammed, many refugees lack English skills upon arrival, making the job search difficult. As a result, according to Donna Duvin, the Executive Director of International Rescue Committee in Dallas, most refugee resettlement agencies offer ESL classes along with the initial aid, such as enrolling students in school, taking the family to the doctor and finding employment.

Many refugees struggle with simple aspects of a new American life. For example, Jim Wohlgehagen, Ph.D., a Hockaday Middle School math teacher who sponsors six Sudanese refugees through his church, brought the boys groceries every weekend while they still looked for work. One weekend, he brought the boys spaghetti and marinara sauce, believing that this dish would be quite simple to make. However, when he returned the following week, he noticed the boys had barely eaten any of the pasta. After he asked why they didn’t eat it, they remarked that they didn’t like the taste of it since they prepared it with sugar.

“These boys had no clue how to take care of themselves,” Wohlgehagen said.

Since the refugee resettlement agencies stress self-sufficiency, the agencies try to find jobs for their clients in their first 120 days. However, in many cultures, women do not work outside the home and thus struggle to act with such autonomy. Michelle McAdam, Job Training and Women’s Empowerment AmeriCorps Associate at International Rescue Committee Dallas, experiences this problem first-hand as she teaches female empowerment classes to refugees and encourages them to find work and leave the house by themselves. While many initially struggle with their fear of more independence, McAdam said that over time “you see the light bulbs come on and you just see them light up to all these different possibilities in the U.S.”

Other problems faced by refugees stem from their ignorance and aversion towards various welfare programs. Sandy Stroo, a Hockaday ESL teacher, remembers tutoring a Russian refugee family in Chicago in English every weekend.

“They asked me one time if I would be willing to drive them somewhere, and they wanted to trade in their food stamps because they weren’t using them all. They wanted cash instead,” Stroo said. “You have to understand that in other cultures, this is pretty much the norm. They didn’t realize this was misuse of government help.”

Others, such as Raul Valdez, a former ESL student of Stroo at University of Texas at Dallas, do not want government aid at all as they do not want to appear as leeches on the government. As a salsa musician from Cuba, Valdez traveled to the United States twice, first to attend a music workshop and second to attend college. Valdez recognized that he could have established residency as a refugee the moment he arrived on U.S. soil through the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966. However, determined not to take advantage of the system, Valdez followed the official procedure, never accepted any welfare and even denounced the label of refugee.

“I did not use the benefits of the government. I did not get any help from the government whatsoever,” Valdez emphatically said.

The stigma surrounding the term “refugee” extends beyond the internal conflict of assuming an inferior position. It often results in discrimination as Mu Naw Di, a high school senior at Bryan Adams High School and Burmese refugee, can attest to. Tearing up, Naw Di recounted her traumatic experiences of bullying that persisted throughout her time in middle school.

“I got bullied when I first came to school just because I don’t speak English. Other students and their words can still give me hard times,” Naw Di said.

However, after three to four years, Naw Di learned that she needed to speak up for herself if she wanted to become a thriving member of society, so she now always responds whenever someone bullies her. As Naw Di illuminated, although ultimately achievable, overcoming obstacles as a refugee in America often requires hard work and commitment to success.

Linda Evans, the founder and chair of the U.N. Association Dallas Chapter Committee on Refugees, said, “[refugees] are not what many people perceive to be helpless, downtrodden people. They are resourceful, they are resilient, they are hardworking and they have a strong motivation to contribute to the communities where they are resettled.”

Trump’s Executive Order and the Aftermath

On Jan. 27, Trump issued the “Executive Order: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorists’ Entry into the United States.” This decree suspended all refugees for the next 120 days so that the current administration could examine its policies. It also placed an indefinite ban on Syrians and a 90 day travel ban on citizens from seven “terror-prone” nations: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

Trump has also capped the number of refugees for 2016-2017 to 50,000, a significant decrease from Obama’s goal of 110,000. However, supporters of the ban have compared Trump’s value to that of Obama’s in 2013-2014, which was approximately 70,000.

Those in favor of the ban, such as Texas Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, argue that the restrictions allow for an increased vetting process. In a statement posted on his website, Cruz said that “I commend President Trump for rejecting Obama’s willful blindness, and for acting swiftly to try to prevent terrorists from infiltrating our refugee programs. In contrast to the hysteria and mistruths being pushed by the liberal media, President Trump’s executive order implements a four-month pause in refugee admissions so that stronger vetting procedures can be put in place.”

On the other hand, others such as Hockaday senior and chair of the Student Diversity Board, Sahar Massoudian oppose this ban.

“Especially the fact that I am a dual-citizen that was for me living in America one of my big connections with Iran,” Massoudian said. “It is not the ban itself, but the fear that two days later I won’t know what will happen with these executive orders being handed out like crazy.”

On Feb. 1, while at the gym, Massoudian looked up from the treadmill toward the television, on which newscasters reported an imminent war with Iran. Massoudian almost broke down crying. She thought about her Iranian uncle, who has lived in the United Kingdom for the past few years. His daughter recently had a son in the U.S., and now as a result of the ban, he cannot travel to see his new grandson. With tears forming in the corners of her eyes, Massoudian asked in a shaky voice, “What have the people done to deserve this?”

Former President Barack Obama designated the seven nations restricted under the executive order as “countries of concern” and placed limited travel regulations on these nations. However, Trump escalated these actions through his executive order.

More notably, Trump excluded Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, all of which have citizens involved in the 9/11 attacks. Critics and ethics lawyers question this decision since the first section of the executive order directly refers to halting terrorism similar to that of 9/11. Many wonder whether Trump deliberately omitted these nations from the ban due to his business interests there.

For example, in an interview with CNN, Richard Painter, the chief ethics lawyer in the George W. Bush administration, noted, “Somalia is on the list, but Saudi Arabia is not. People from Somalia are going to say that’s arbitrary. And one of the factors, people are going to say, is the president does business with Saudi Arabia but not Somalia.”

Although the exclusion of certain countries has raised questions due to Trump’s business interests, the legality of the executive order may raise more concerns. In a joint statement, 16 Democratic state attorney generals stated that they “condemn President Trump’s unconstitutional, un-American and unlawful Executive Order and will work together to ensure the federal government obeys the Constitution.”

Judges, too, have expressed their consternation toward this order. On Feb. 3, 9th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge James Robart in Seattle ruled for a temporary halt on the enforcement of Trump’s executive order, which the Department of Homeland Security later endorsed. Trump took to his favorite media platform, Twitter, to proclaim that “The opinion of this so-called judge, which essentially takes law-enforcement away from our country, is ridiculous and will be overturned!”

On Saturday, Feb. 4, the Trump administration and the Justice Department appealed the State Department’s actions to temporarily block his executive order; however, it was denied.

Despite the courts deeming it dilatory, many have still taken to the streets and airports across the world against the ban; however, others, like Hockaday’s math teacher Wohlgehagen, do not understand all the backlash. He sees the executive order as a temporary attempt to fix a broken immigration system and also wonders where support for refugees was during the Sudanese refugee crisis 20 years ago.

“It kills me that all these people are out here protesting. Where were they when these boys were being killed and when they were put in a refugee camp?” Wohlgehagen said.

Wohlgehagen is not alone in his frustration toward the protesters. In fact, according to a Jan. 30 Rasmussen Reports survey, 57 percent of likely voters support the executive order. But a Fourcast survey of 194 Upper School students and members of the faculty and staff yielded drastically different results. Of those surveyed, 85 percent opposed the ban while only 12 percent supported it.

What Happens Next?

In response to Trump’s executive order, communities across the nation have mobilized in support of the refugees. On Jan. 28, 800 people protested at the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport while they waited for the release of Sumira Mustafa’s elderly diabetic mother, who traveled from Sudan. Doug Parker, CEO of American Airlines Group, Inc., said to The Fourcast that the protesters made it difficult for passengers to check in and for the flight staff to do their jobs. Parker said that he advised his employees “to be respectful and to not be divisive.”

In a statement released to employees of American Airlines, Parker said, “As a global employer, however, this Executive Order does not affect the values that this company is built upon – those of diversity, inclusiveness and tolerance. At a time when the world is watching, our industry affords us a unique opportunity to show firsthand what true compassion and kindness look like.”

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings attended the protests at DFW airport to bringing flowers to the detainees.

“As a Christ follower, I believe in welcoming and helping the most vulnerable. Opening our doors to refugees is good for business and the economy, but more importantly, it is good for the heart,” Rawlings said to The Fourcast.

And approximately 1,600 people, according to the event’s Facebook event, attended a candlelight vigil in Dallas’ Thanksgiving Square to “show support for Muslims, refugees, and immigrants in the Dallas community.”

Aside from these demonstrations, local nonprofits and resettlement agencies are trying to take quick action to provide as much aid as they can to those already in the country. Leala Rosen, the Volunteer Outreach Manager at Vickery Meadow Learning Center, said that VMLC has already taken steps to help their refugee students after noticing some of her students’ fears about the executive order.

“I think for all of our refugee students that there is concern in their daily lives. I feel like they have some unease and anxiety about what will happen, so we are really working to support our students,” Rosen said. “We are going to do ‘Know Your Rights’ presentations that includes all of our students, including our immigrant students. So the ACLU and other organizations do a ‘Know Your Rights’ presentation to explain the steps to take if you are detained.”

While resettlement agencies always need donations and supplies, McAdam of the International Rescue Committee has simple advice for those interested in helping refugees: advocate for refugees and educate others about them.

“Do not be afraid of what other people are going to say. Spread the truth. Spread the facts. Let people know the reality of refugee resettlement in the United States,” McAdam said.

Katie O’Meara – Photo & Graphics Editor

Mary Orsak – Asst. News Editor

Linda Abramson Evans

Feb 12, 2017 at 2:37 am

Mary Orsak and Katie O’Meara, this is exquisite journalism and a true service to the refugee community. It was a pleasure to spend the time with you. Mary, glad you could attend our refugee services panel on February 4 and interview Michelle, also. I will share the article with all agencies in the Dallas Area Refugee Forum and Metroplex Refugee Network, as well as community organizations and advocates. (For readers who would like to volunteer, the website below includes a link to the “Volunteer Guide to Refugee Service Agencies in Dallas/Fort Worth.”) Brava, and please stay in touch!

gretchen bohnert

Feb 10, 2017 at 4:47 pm

Orsak’s column on refugees was fact-filled and had a Dallas focus that made it unusually interesting and apt. Keep up the good work.

G. Bohnert