In the fall of 1971, a group of rebellious teenagers, known as the “Waldos,” embarked upon a fateful journey that has since defined rap music, Seth Rogen movies and youth culture. These students of San Rafael High School in California met each other outside school one afternoon at 4:20 and set off to discover the greatest treasure the decade had to offer: marijuana.

Although these rebels never found the plot of marijuana at Point Reyes, the term “420” has persisted within the youth lexicon to such a degree that individuals around the globe commemorate these fallen heroes on April 20 every year with a joint.

Cultural fascination regarding marijuana permeates farther than California in the 1970s. One Hockaday student, who agreed to speak under terms of anonymity and who classifies her use of marijuana as “social,” said that “being in high school, you are exposed to so many things. Teenage curiosity leads you to maybe experiment a little bit.”

However, marijuana usage is no longer restrained to “teenage curiosity.” A 2016 Gallup poll showed that 43 percent of Americans have tried marijuana and 13 percent smoke the drug regularly.

As American cultural acceptance of marijuana grows, politicians around the world struggle to address the phenomenon. The Canadian and Uruguayan governments responded by legalizing recreational use of the drug; on the other hand, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced on May 12 that he planned on stepping up the “War on Drugs,” a term popularized by former President Richard Nixon ironically in 1971—the same year the Waldos became cultural icons.

Dallas Joins the Discussion

On April 12, the Dallas City Council weighed in on this national debate. In a vote of 10 to 5, the Council approved a measure allowing police officers to issue a citation and then release individuals found with less than four ounces of marijuana, rather than immediately taking them to lockup. While those in possession of marijuana will not immediately face punishment, they still must attend an arraignment hearing and may receive jail time, probation or a fine depending on the judge’s sentencing.

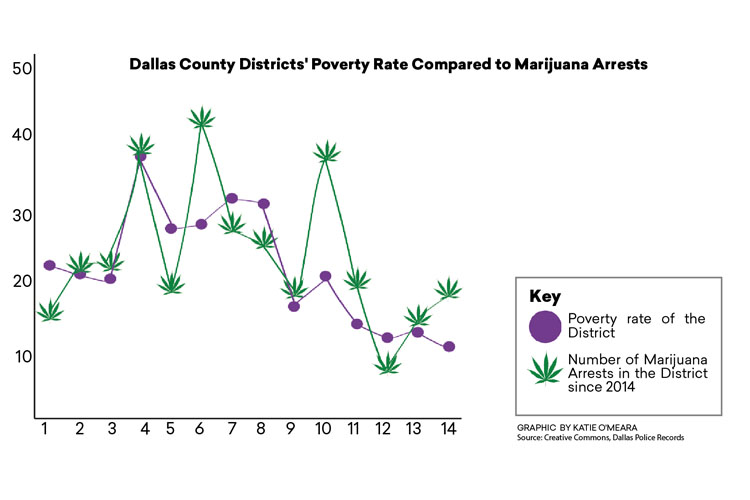

Council Member Philip Kingston led the charge on this city ordinance because he believes that “from the very beginning, laws restricting access to marijuana are racist and are enforced in racist ways.”

Kingston makes a valid point. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, while marijuana use occurs in equal amounts in both black and white communities, African Americans are 3.7 times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts.

When prompted about whether the Dallas Police Department racially profiles citizens in regards to marijuana arrests, Kingston bluntly stated, “We know it does.”

City Council Member Rick Callahan, however, disagrees with Kingston.

“I get frustrated when I hear that [marijuana laws target African Americans],” Callahan said. “I don’t think there is any evidence.”

This is not the only marijuana-related issue on which the two council members diverge. Kingston, unlike Callahan, sees no negative health repercussions of marijuana use.

“I also don’t see any peer reviewed research that shows that marijuana has any negative health effects. I don’t think there is a correlation with schizophrenia,” Kingston said.

Sidarth Wakhlu, M.D., who currently works at UT Southwestern Medical Center as an addiction psychiatrist, has ample evidence to the contrary.

“Clearly, marijuana is less lethal drug when you compare it to heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine, but it is not benign,” Wakhlu said. “It is not a herb.”

What worries Wakhlu the most is the rising percentages of Tetrahydrocannibol, the psychoactive chemical in marijuana. In the 1980s, most recreational marijuana had a THC content of only 2 percent; now, that value has risen to 15 to 20 percent. Why does consumption of THC matter? A plethora of studies prove a correlation between THC and bipolar disorder with psychotic features.

Wakhlu says that he sees every month “at least one or two young adults who are recently discharged from the psychiatric in-patient [facility] at Zale [Lipshy University Hospital] because of a marijuana induced psychosis.”

In addition, a study by two Australian professors—Wayne Hall of the University of Queensland and Louisa Degenhardt of the University of New South Wales—showed that 13 percent of schizophrenia cases could be averted if these patients did not use marijuana.

To Kingston, who denies both the existence and validity of these studies, evidence against marijuana is simply driven by “a lot of politically motivated people that want there to be negative effects” in order to continue locking up minorities.

Those like Wakhlu, who cite the physical and mental side effects of marijuana, are not the only critics of the ordinance. Callahan and Council Member Jennifer Gates both opposed the proposal because of the four ounce threshold.

For example, Callahan does not oppose the infrequent usage of small amount of marijuana.

“Four ounces is too much. It sells for about $300 to $400 on the street. That goes beyond personal consumption,” Callahan said.

For reference, assuming each joint contains about 0.5 grams of marijuana, four ounces would supply enough drugs for approximately 226 joints.

What’s next?

Despite these objections from Callahan, the ordinance will go into effect on Oct. 1. The question that now largely remains is how this new ordinance will affect marijuana policing and consumption.

Kingston hopes this cite-and-release program will usher in an age of de facto decriminalization. Since he cannot change the state laws that would allow for decriminalization, Kingston aimed to create a program so tedious that police officers would slowly begin to stop arresting individuals with under four ounces.

Kingston sees this as an opportunity to free up police officers’ time “even more so than the police [believe will happen].”

Callahan remains dubious of this conclusion. Arguing that police only spend about 2 percent of the time dealing with marijuana possession, Callahan perceives that little change will occur in the lives of police and finds arguments that reducing police workload will allow them to catch “the real bad guys” is simply fallacious.

The other debate about the consequences of the ordinance focus on how it may affect marijuana usage.

When prompted about whether the new ordinance would significantly alter usage, she responded, “Well, yes and no. I think that people seeing that the government is making this law will make people rethink their opinions on it… However, in my experience, it will probably not change the amount anyone smokes.”

A 2015 study in The Lancet Psychiatry Journal supports this statement. A comprehensive analysis of usage in states with legalized medical marijuana proved no correlation between lenient laws and increased usage among teens.

Ultimately, this new ordinance pales in comparison to actions taken by other cities and states. Houston, for example, effectively decriminalized possession under four ounces by allowing police officers to confiscate the contraband and instruct the individual found in possession to attend a four-hour drug safety course.

Callahan believes that Dallas will likely follow Houston’s lead in five, seven or even 10 years, but in the meanwhile, possession will remain a Class B offense, and modern Waldos will need to celebrate April 20 discreetly.

Mary Orsak – Special Magazines Editor