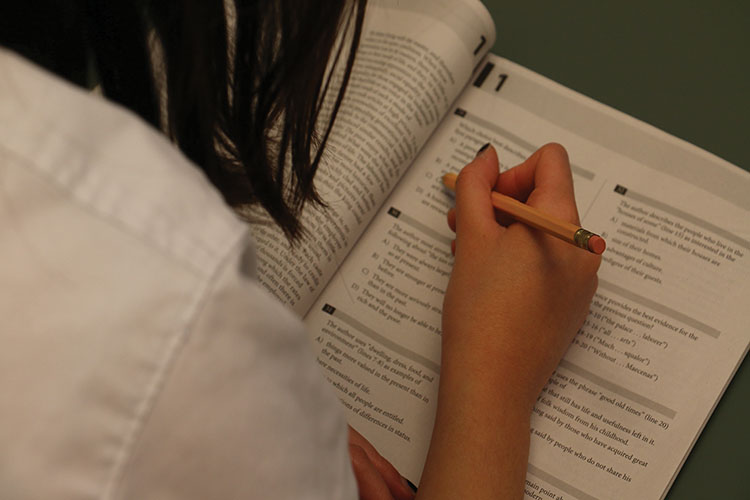

PICTURED ABOVE: Starting as early as Lower School, Hockaday students begin standardized tests. Director of Learning Support Shelley Cave notes that these types of tests often provoke anxiety in even the youngest students. Photo by Kate Woodhouse.

After the hypnotist turned off the lights, then junior Katie Vanesko reclined in her chair while snuggling with a blanket. She listened carefully to the soothing intonation of psychologist Dr. Carl Ward’s voice until her eyelids grew heavy and she could no longer stave off the tempting lure of slumber. After some time, Vanesko shook off the shackles of sleep and left Ward’s office without any noticeable change. For the next three weeks before the impending ACT test, Vanesko replayed the recording of her session with Ward as she fell asleep. Then on that fateful morning of April 8, 2017, Vanesko recognized that her typical testing anxiety vanished.

“I got there and everything was easy. All the things that I had struggled with before like doubting myself, it wasn’t there. I didn’t worry about the time as much,” Vanesko said.

Prior to undergoing hypnosis, Vanesko met with an ACT tutor every Tuesday afternoon and frequently took mock exams at Slingshot Test Prep on Saturday mornings. Each time she finished the exam, Vanesko received the same score despite studying several hours a week.

Frustrated with her progress, Vanesko decided to resort to an unconventional preparation method: hypnosis.

Although rarely discussed, students have increasingly relied upon hypnosis to alleviate test anxiety and, in turn, improve test scores. A survey of 33 Hockaday seniors found that almost 10 percent of students had undergone hypnosis for test anxiety, and more than 50 percent of the 177 underclassmen remained open to trying hypnosis.

Ward defines hypnosis as “a state of deep relaxation in which the subconscious mind becomes more available for suggestion.” His sessions, which last from 30 to 50 minutes, begin with the patient sharing his or her particular anxieties and then end with the hypnotic session, in which Ward counteracts negative thoughts through targeted messages.

Although anxious high schoolers only comprise a small percentage of his practice, Ward, a psychotherapist who has practiced hypnotherapy for 25 years and who served as the president of the North Texas Society of Clinical Hypnosis, has become a valuable resource to many standardized test tutors who rely upon his services to reduce anxiety in their students.

“Years ago, I hypnotized some medical students and they did much better and so the word got out to these North Dallas tutors,” Ward said.

Ward credits the increase in stress to the rising college admission standards and the competition to attend the most prestigious universities in the country.

“These people want to get into these colleges and want higher and higher ACTs and so hypnosis—it won’t make them do well in math if they don’t know math and it doesn’t replace studying—but what it can do is get more out of yourself,” Ward says.

Vanesko desperately wanted to add one more point to her composite ACT score in order to make herself a more competitive candidate at her dream school, but her anxiety about timing precluded her from getting that extra point.

“I just got really nervous when I was taking the full test. I would get really stressed out about time,” Vanesko said.

Dr. Avery Hoenig, a licensed psychologist who treats adolescents and adults with anxiety and depression, has observed anxiety about school and the college admissions process in nearly 100 percent of her high school patients.

“I would say that the main cause of anxiety is stressors so mostly within the academic realm, you can see test anxiety, which is more of specific stress or anxiety about performance on a test,” Hoenig said. “More often there is just an overall feeling of being overwhelmed.”

When Hoenig first sees a patient with test anxiety, she discusses whether testing accommodations like taking the test alone or receiving extra time would help assuage some of the anxiety. If that is a not a viable solution, Hoenig progresses to cognitive behavioral therapy, which teaches patients problem-solving skills and healthy ways to cope with stress. If that then fails as well, Hoenig may refer a patient to a psychiatrist, who could prescribe anti-anxiety medications.

Ward, on the other hand, approaches test anxiety differently and views cognitive behavioral therapy, which Hoenig practices, as too time intensive. Instead, Ward has a preliminary diagnostic meeting with the patient and his or her parents to assess whether hypnosis will benefit the patient and then proceeds with hypnotherapy.

According to a report produced by researchers at Stanford University in 2000, only 10 percent of the population is highly hypnotizable although a greater percentage has the ability to undergo hypnosis. Despite this statistic, Ward assumes that every patient is a good subject for hypnosis.

“I don’t believe that 10 percent thing. Those things are researched at universities by people who do not practice,” Ward said.

Ward contends that hypnosis is far more effective than more traditional methods of therapy.

“The quickest way to help somebody is using trance work. When you are dealing with something as powerful as anxiety, [cognitive behavioral therapy] is much less effective,” Ward said. “In terms of stabilizing a personality with anxiety, CBT [cognitive behavioral therapy] is very good. In terms of providing something that gives them pretty quick help and getting back to being able to manage that level of anxiety, trance work is much more powerful.”

Hoenig has never referred a patient to a hypnotherapist because “while I certainly don’t want to discount [hypnosis] because it can be helpful, it is something that the jury is still kind of out. There are not a lot of peer-reviewed articles about short-term or long-term benefits of hypnosis.”

Ward disagrees with this assertion and said, “Hypnosis is accepted by all the professional organizations now. There are hundreds of books and thousands of scientific studies validating the use of hypnosis.”

Regardless, the word “hypnosis” still evokes images of performers instructing unwitting audience members to cluck or fall asleep at a snap of the hypnotist’s fingers. Every time a patient enters his office, Ward must explain that hypnotherapy greatly deviates from its depiction on television.

Vanesko experienced this same scepticism about hypnosis even though her brother had used it to help with both his sleeping problems and his test-anxiety.

“I didn’t really trust it. I mean, it worked for my brother, so maybe it is not just some weird dude with a crystal ball, but I was skeptical,” Vanesko said.

Even after the hypnosis, Vanesko refrained from sharing her experience because she believed her friends may judge her for utilizing an unorthodox treatment.

“It was embarrassing. It’s like weird,” Vanesko said.

Despite her uneasiness about discussing hypnosis, Vanesko did improve her ACT score by one point. However, Vanesko is not certain that the hypnosis alone earned her the point.

“I credit my sessions with Dr. Ward, but I don’t think it was hypnosis. I don’t think I was hypnotized,” Vanesko said.

Vanesko does still recommend meeting with Ward if you suffer from test-anxiety because his sessions train patients to believe in their own ability and remind them that they will survive even the most traumatizing test experience.

“Honestly, it costs the same as one tutoring session,” Vanesko said.

Hoenig simply recommends treatment for anxiety, regardless of what treatment one chooses.

“I do think that anxiety seems to be on the rise, and I think that it is important to know that there is help and treatment available. If hypnosis is helpful to you, that’s great. If that’s not working for you, [Dallas] has great mental health practitioners,” Hoenig said. “There is help available. There is no need to suffer in silence.”

Story by Mary Orsak, Special Magazine Editor