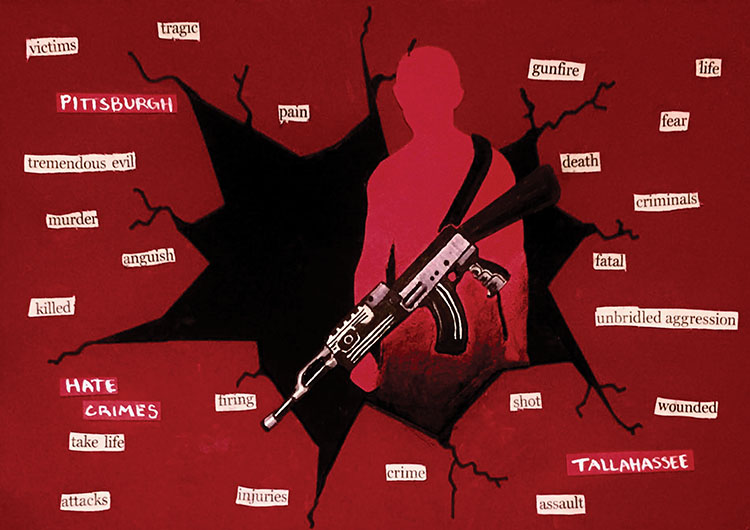

News stations and outlets are constantly inundated with news about hate crimes, but what exactly defines a hate crime? These offenses can fall under many names, such as terrorism, mass shootings or attacks, but hate crimes are set apart by some defining characteristics. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender or gender identity.”

Hockaday Pride Club and Student Diversity Board member junior Anika Bandarpalle agrees with this definition; that hate crimes are based around a victim’s identity.

“To me, I think of race, religion and sexual orientation [when thinking of hate crimes] because those are a part of you that you can’t change,” Bandarpalle said.

The discussion after a hate crime often turns to discourse over gun control or the difference between political parties’ responses. However, regardless of bipartisan politics or gun control, there has a been a shocking increase

in hate crimes in the United States in recent years. According to The New York Times, hate crimes in the U.S. increased by 17 percent in 2017, with 7,175 reported hate crimes compared to 6,121 in 2016. With a 23 percent increase in religion-based hate crimes, many religions are faced with the issue of how to respond to violence and threats against their communities. According to a FBI report from early Nov. 2018, there was a 37 percent increase in anti-Semitic hate crimes in 2017 and more than 900 reports of crimes targeting the Jewish community and institutions last year alone.

The FBI report also revealed a recent increase in hate crimes against the African-American community, in fact, a 16 percent rise from 2017. According to National Broadcasting Company (NBC), “black Americans have been the most frequent victims of hate crimes in every tally of bias incidents generated since the FBI began collecting such data in the early 1990s.”

Recently, there has a been a call for the U.S. government to update its laws and put hate crimes under the same category as terrorist attacks — those that are motivated by radical international groups such as the Taliban. Currently, many hate crimes are not classified as terrorism if they are committed by white Americans, or they are labeled as domestic terrorism but still not taken as seriously. However, the Government Accountability Office reported in 2017 that since the attacks of 9/11, “far-right extremists committed almost three times as many attacks—62, compared with 23 by Islamist extremists.” Similarly, The New York Times reported that white supremacists and generally far-right extremists killed “far more people since Sept. 11, 2001, than any other category of domestic extremist”.

However, “the language [of government counterterrorism] heavily focused on recruitment and radicalization by ISIS and Al Qaeda,” Nate Snyder, a counterterrorism advisor to the Obama administration at Homeland Security in an interview with The New York Times said.

This lack of oversight regarding the increase of far-right extremism has frequently been seen as a contributing factor the general rise of hate crimes, as the majority of hate crimes have been committed by far-right extremists.

Hockaday English teacher and Black Student Union sponsor Summer Hamilton believes that the government’s response to any hate crime should be firm.

“I think that for impressionable people there should be a swift and clear denouncement. Ambiguity is dangerous,” Hamilton said.

So why and how have these attacks increased so sharply in recent years? Many say that the rise of hate crimes could be attributed to growing nationalism in the U.S. and many other countries. According to BBC News, several European countries have seen political gains for nationalist parties throughout 2017 and 2018. While many of these countries’ purely nationalist parties may not have won the majority in elections, the percentage of voters for these nationalist parties has increased in parallel to a rise in hate crimes. For example, the nationalist Swiss People’s Party won 29 percent of the votes in Switzerland’s most recent national elections. Many news stations and experts on the topic point to anti-immigration sentiment (similar to the anger that partially fueled Brexit) for this rise in nationalism.

Cultural shifts stand as another potential factor of the rise of hate crimes in America. Hamilton thinks how we treat prejudice has changed in current culture.

“I think now there is less pressure to cover one’s hatred under the guise of freedom of speech or ‘two sides to every opinion’. Because there is no longer a stigma attached to expressing one’s hatred for a group, that [hatred] can spread, especially quickly with technology,” Hamilton said.

Head of the Hockaday Student Diversity Board, Tanvi Kongara points to polarization as a catalyst for the recent rise in hate crime, and advises talking to other members of one’s community as one way to combat general polarization.

“One of the main reasons we think forums are so effective is because discussion is honestly the best way to understand other people’s perspectives,” Kongara said.

Some consider affinity groups and student unions more important than ever in the face of a rise in hate crimes. Bandarpalle believes that these groups give a voice to traditionally marginalized groups.

“It is also a really great opportunity for people in those communities to educate our peers because I think that education leads to empathy, and empathy is really important given the polarized climate right now,” Bandarpalle said.

Hamilton thinks that while talking about hate crimes is very important, affinity groups are also important as forms of refuge.

“[At the Black Student Union], there is some discussion of issues and problems that the community faces, but it is also a time of coming together and maybe finding resistance through joy and sort of just enjoying the company and the space to be free,” Hamilton said.

It can be easy for one to become desensitized to hate crimes and the sheer scale of them, but Bandarpalle and Kongara agree that discussions are still important.

“The reality is that there is someone in our community that feels personally hurt by that,” Bandarpalle said in regards to response after the news of a hate crime.

It seems that there are many concrete factors for the rapid increase in hate crimes, but as one can see in the Hockaday community and in the country as a whole, potential solutions are extremely different and still evolving.

Story by Niamh McKinney, Arts and Life Editor

Illustration by Kemper Lowry