PICTURED ABOVE// Prime Minister Theresa May gave a speech at Lancaster House on 17 January, 2017 about the government’s 12 priorities for negotiating the UK’s exit from the European Union.

British Prime Minister Theresa May proposed a new Brexit plan to Parliament on Jan. 21 after a historic defeat Jan. 15, with 432 Members of Parliament (MPs) voting against her deal and 202 MPs for it. Parliament will vote on May’s Plan B on Jan. 29.

Here’s everything you need to know about this chaotic period in British politics.

What is Brexit?

“Brexit”, a mashup between the words “Britain” and “exit”, refers to the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union as a result of a referendum held on June 23, 2016. A referendum is a general vote by the public on a single political question, and in the Brexit referendum, voter turnout was 71.8%, with over 30 million voters. Ultimately, leaving the EU won by 51.9% to 48.1%.

What has happened so far?

After the referendum, the UK triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which gave the UK two years to negotiate an exit deal, which outlines the terms of the split. May started this process on March 29, 2017, so the UK is scheduled to leave the EU March 29, 2019. If her deal had passed, a two-year transition period would begin: the UK, under the same rules, would negotiate different trade relationships with the EU before Dec. 2020. After that, the UK would no longer be subject to EU regulations.

What are some major issues still being debated?

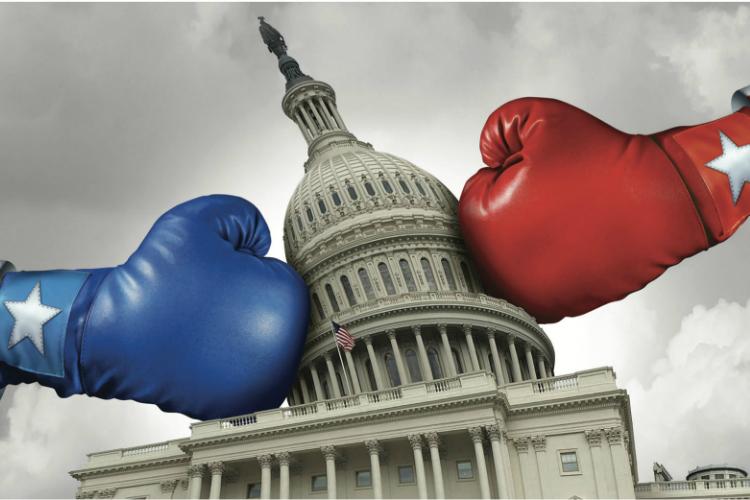

Key contentions of the withdrawal agreement center around whether the UK should make a more dramatic break with the EU or a softer one that would allow the UK to maintain a closer relationship with the EU. The MPs that rejected May’s deal raise a myriad of objections surrounding economics, free movement of people, court regulations, and trade.

“Ironically, some of the issues being debated in Parliament are the same as those being talked about here and the rest of the western world,” Steve Kramer, History Department Chair, said.

The pro-Brexit parties emphasize closing borders and protecting jobs for citizens of the UK, according to drama teacher Emily Gray, who lived in the UK until she was 27. They are also concerned that the UK provides too many resources to the EU to bolster other member states. “What they don’t realize is, while you pay more in, you get more out,” Gray said, “so for example, Britain would pay more into the EU, but get massive farming subsidies.”

On the other hand, anti-Brexit parties argue that Brexit would inhibit trade, as passports and visas would be needed to cross international borders. Others contend that by remaining in the EU, the UK has more power on a global scale.

What do Hockaday students and faculty think about Brexit?

“I think it is absolutely the wrong thing for Britain, and it’s a very short-sighted non-solution to what people are citing as Britain’s problems,” Gray said.

Hockaday senior Sophie Dawson was in the UK recently and talked to high school students applying to Oxford for politics and economics. The topic came up when someone had asked her about Trump, and she had responded by questioning them about Brexit.

“Both questions have the same weight, that same contentiousness,” said Dawson, “the general sentiment among kids our age was ‘why in the world did this happen in the first place? Why are we in this situation?’”

Dawson had also lived in the UK when she was younger. Because she was in fourth grade at the time, she had little understanding of the EU but enjoyed the advantages that it had offered. “You can hop on a train and go to Paris for a day trip,” said Dawson, “so that free movement of people was something that I saw the benefit of.”

What are the possible endgame scenarios?

So far, the future of the UK is unclear. May’s new deal may be accepted by Parliament, which would allow the UK to leave March 29. Or, the government may hold a second referendum, a once unthinkable option that some political leaders are now calling for. However, the efficacy of a referendum is disputed. Kramer cited the Colombian FARC referendum, attributing its failure to its low voter turnout, which was influenced by the bad weather that day.

If the government is unable to reach an agreement, revoke or extend Article 50, there will be a “no deal” – that is, the UK will leave the EU with no terms, resulting in an abrupt rupture in UK/EU relations and no transition period.

Story by Kelsey Chen, Staff Writer

Photo provided by Flickr