It’s a sunny Monday morning, and 8-year-old Abby has just arrived at school with a full stomach and fresh excitement to conquer the day. In another school across town, 8-year-old Anna is stepping onto the grounds, hungry, unprepared and exhausted from doing nothing but watching T.V. all weekend. Before Abby left for school, her parents checked her homework and packed her a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch. But before Anna left for school, she had still not completed homework and did not have breakfast because her parents had already left for work. Now, her only hope is that the lunch provided by the school is good today.

In the classroom, Abby’s teacher uses tablets to instruct the students and projects videos onto the board. The air-conditioned classroom has brand-new desks with chairs and is filled with colorful, informational posters and interactive physics models. Anna has to take notes from an old chalkboard that barely has enough chalk. Her shabby classroom, with flickering lights and leaking ceilings, makes it difficult—nearly impossible— for her to concentrate during the lesson.

Abby and Anna have vastly different experiences educational experiences, but why? The answer: their location. Because they were born into neighborhoods with different socioeconomic statuses, their opportunities in school—and even in life—are affected by five numbers tacked onto the end of their addresses.

THE PROBLEM

In 21st century, life’s competition begins as early as infanthood. As soon as a child is born, he or she will be immediately assigned to a predestined path. While some children are lucky enough to be born into a middle class, comfortable family with caring parents and a safe home environment, others face poverty, a lack of parenting and unimaginable trauma. Otherwise known as the “zip code lottery,” the children who were born into a less affluent neighborhood must overcome the unfavorable odds to succeed when it was just by the roll of a die that they were born into that socioeconomic class in the first place. Hockaday’s Director of the Institute of Social Impact Laura Day echoes the random nature of the opportunity gap. “The opportunity gap is based on no choice of your own and based on where you’re born, how or what you are born into, some people are provided access and resources that others aren’t,” Day said.

Education researchers at the University of Kansas, Betty Hart and Todd Risley, have constructed three broad classifications based on socioeconomic status that American families fall into. This, in turn, helped them discover the far-reaching impact that one’s family environment can impose on children. Their research indicates that as early as the age of four, children that belong to low socioeconomic status will already have a word gap of up to 30 million words from their more well-off peers. This unimaginable 30 million words actually comes from the daily accumulation of words used in a family’s routines. As a consequence, a family’s socioeconomic status is the first determining factor that shapes a child’s future, granting the “winners” of the zip code lottery earlier access to the world’s resources, but dragging those who have already fallen behind even further down.

By this point of a child’s life, the opportunity gap has already unveiled its unfairness. Access to healthier food and early childhood education compound together to build an insurmountable mountain between children of different classes. The opportunity gap enlarges as each child ages, and by the time children enter school, the victims of opportunity gap have found themselves even more disadvantaged in comparison to their peers. This problem extends far beyond just the scope of school. “Some people are born into a neighborhood where there isn’t any grocery store within 3 miles and their family doesn’t have a car, and the public school is failing, and some people are born into a neighborhood where that’s not the case,” Day said.

The turning point comes at third grade, a time that marks a key periodic difference between individuals’ academic performances. By third grade, affluent children are in the lead for up to an entire school year, advancing with the help of high-quality summer activities, enriching experiences and an abundance of other opportunities. In comparison, students of a lower socioeconomic standing are behind the curve. In the third grade, the teaching style shifts from “learning to read” to “reading to learn,” so these students will miss out on lessons on reading techniques and subject matter. If students are not reading by third grade, it becomes increasingly unlikely they will ever catch up to their peers who can read. According to Day, third grade reading not only indicates the children’s access to educational resources throughout infanthood and childhood, but also measures a child’s potential development.

“[Third grade reading] is the biggest indicator researchers found for high school and college readiness,” Day said. “If you’re caught up in reading on grade level by third grade, there’s such a higher percentage that you’re going to be college-ready, and you’re going to make it through high-school at the age appropriate [time].”With such dramatic differences already present among children, the damage caused by the opportunity gap is irrefutable. But, as problem solvers and educators examine the root of the disparity, the fundamental cause of the problem appears to be even more complicated to tackle.

As a matter of fact, history has played a large role in opportunity gap causing profound and long-term harm to the modern society, especially in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The past ghosts of segregation have sowed the seeds of education disparity. Jonathan Feinstein is the Director of Community Engagement of The Commit Partnership, a non-profit organization that aims to cooperate with Dallas-Fort Worth schools and school districts to address opportunity gaps, and believes that public schools play a large role in maintaining or closing these gaps.

“The opportunity gap goes back as far as public education has ever existed,” Feinstein said. “And it continues in today’s schools, which are still largely segregated, despite the 1954 Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education, which declared legally segregated schools to be inherently unequal.”

However, under the past shadows of segregation that roam Texas, this phenomenon gradually resembles a newer form of segregation in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In Dallas Independent School District (DISD) schools, where students of color compose a majority of the student body, poverty and lack of resources are still posing challenges. President of the DISD Board of Trustees Dr. Edwin Flores comments that Dallas public schools have more impoverished students than in Detroit public schools. “Over 90 percent of our students are on free or reduced cost lunch, which means they’ve met a federal standard of poverty,” Flores said. “And 95 percent of our students are either Hispanic, African Americans or other ethnic minorities.”

In addition to being faced with poverty, children are also confronted by numerous other obstacles. For some students of immigrant descent, language barriers can add to the challenges. “[More than half of] our Hispanic students, [who are] above 70 percent of our student body, or about 50,000 students, don’t speak English at home,” Flores said. “We have a combination of poverty and challenges to confront every day in our classrooms for those students who don’t speak English at home, but we don’t apologize for our demographics.” With such difficulties hindering the ability to eliminate the opportunity gap, challenges such as language barriers or family environments both demand time and effort to tackle. To prevail in this tug of war, schools and organizations must take action. Fortunately, they are on the right path.

THE SOLUTION

As more and more research has been published about the disparity of opportunities between kids of varying socioeconomic classes, organizations, school districts and private schools have decided to change the narrative. DISD has implemented many new policies in order to ameliorate the disparity.

In 2006, DISD went district-wide with two-way dual language learning, where English language learners and fluent English speakers learn to read and write in both English and Spanish. By the end of the dual language program, students will be fluent in both languages. It also allows African American students to learn a new language fluently. According to Flores, since the program’s implementation, there has been a significant increase in student achievement in comparison to the rest of the state because of the program’s rigorous nature. “[The dual language program] is a slightly more difficult path for [students; however] the kids do better without any doubt,” Flores said. This aligns with national data on biliterate students.

DISD has also improved teacher evaluation systems to better serve the students. Currently, the state of Texas evaluates teachers on their attendance, adherence to the dress code and completion of lesson plans, among other things. Since 2012, DISD has developed and implemented the Teacher Excellence Initiative (TEI) to better assess educators. “The methodology used by the state of Texas to evaluate teachers does not measure anything related to student outcomes,” Flores said.

Instead of just one 45 minute observation each year, TEI requires eight, 12 or 16 spot evaluations to assess teachers and help them to improve their skills. After the evaluations, a trained professional meets with educators to give them advice on how to better teach the students and give them resources to implement into the classroom. These observations account for 50 percent of the total evaluation. Thirty-five percent of the TEI evaluation consists of students’ test scores. These tests evaluate whether or not the teacher has taught the students one year of course material. Students take district-made assessments called Assessment of Course Performance, or ACPs, throughout the year and State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR tests. Schools only use the higher scoring of the two to evaluate the teachers. Student surveys complete the final 15 percent of the assessment. Once students reach Middle School, they rate their teacher based on whether or not he or she paid attention to them and helped reach a better understanding of concepts, along with many other classroom aspects.

DISD places teachers that receive high ratings on their evaluations in schools that need the most help. Traditionally, school districts place the least-experienced teachers with the least resources and the lowest-performing students. If these teachers opt to transfer to improvement required schools, they can receive a raise and bring their talents to DISD’s most-needed areas. Four years ago, DISD had 43 improvement-required schools; however, through this program, the school district only has four. “[No urban school district in Texas] has improved the way [DISD] has because nobody else has our teacher evaluation,” Flores said. “Without that teacher evaluation, there is no way you know who the great teachers are put with the kids who need it the most.”

DISD is also pioneering a revolutionary program in Texas: full-day pre-Kindergarten. Currently, the state only funds half-day pre-K for four-year-olds, so this program costs the district $60 million annually. This new program has been instrumental in improving third grade reading scores by preparing students for kindergarten, and therefore the rest of their years in school. “[Full day pre-K] is the only way that our kids can start on grade level to be ready for college or the workforce,” Flores said.

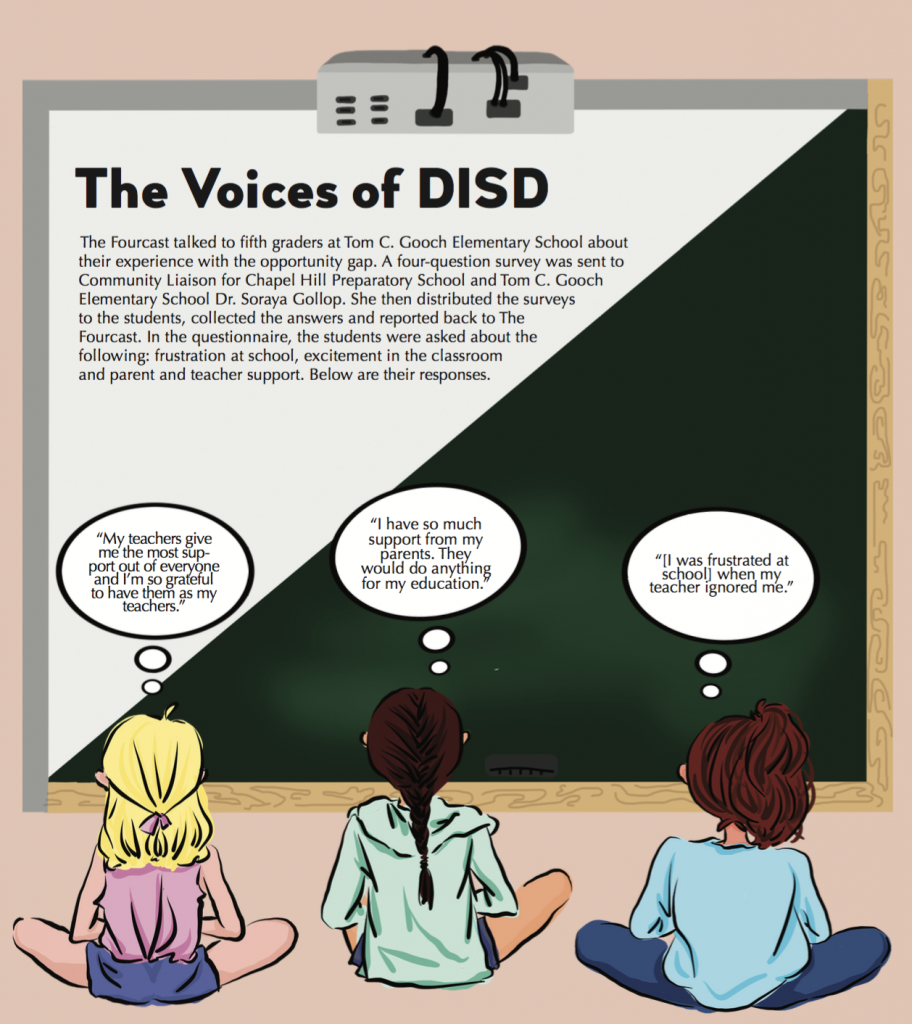

In addition to DISD’s changes in policy to ameliorate the opportunity gap, many private schools, including Hockaday, have begun to use their resources to help the district. Hockaday community service currently serves nine elementary and middle schools. Since 2007, these schools have improved their third grade reading scores by 11 percent, a higher rate than the state of Texas and DISD as a whole. Community Liaison for Chapel Hill Preparatory School and Tom C. Gooch Elementary Dr. Soraya Gollop has seen the great benefits Hockaday has brought to these schools. “Just having that one-on-one tutoring time helps our students greatly with their basic skills, whether they are working with math or reading or both, and that’s valuable,” Gollop said. “Our teachers are great, but they cannot spend one-on-one time with a student. It is just not possible because of the way the classes have to be set up.”Gollop also notices an indirect effect of Hockaday students’ interactions with DISD students: exposure to new ideas and opportunities. In addition to tutoring programs, the Upper School orchestra performs at schools, students come to see Hockaday performances and the Hockaday drama students teach plays to other students. Hockaday’s orchestra hosted a pop-up performance at David G. Burnet Elementary and exposed its students to instruments, like the cello, they had never seen before. After they walked away from the performance, Day noticed first graders telling their teachers that they wanted to play the instrument. Junior and Co-Head of the Gooch Elementary tutoring program Gina Miele recalled the impact that Katie O’Meara ‘18 had on a fifth grader that she tutored last year. At the beginning of the year, the boy believed that he would not go to high school—probably not even finish high school—and just play soccer because that was the only thing he could do well. With O’Meara’s tutoring and mentorship, the fifth grader changed his mindset and wore a “Future Harvard Graduate” t-shirt to the last day of tutoring.“It just shows that tutoring and mentoring kids can really change their perspectives and start to look to the future and feel like they can do more with their lives than they previously believed they could do,” Miele said.

Story by Kate Woodhouse and Emily Wu

Photo by Ponette Kim

Illustrations by Karen Lin and Cindy Pan