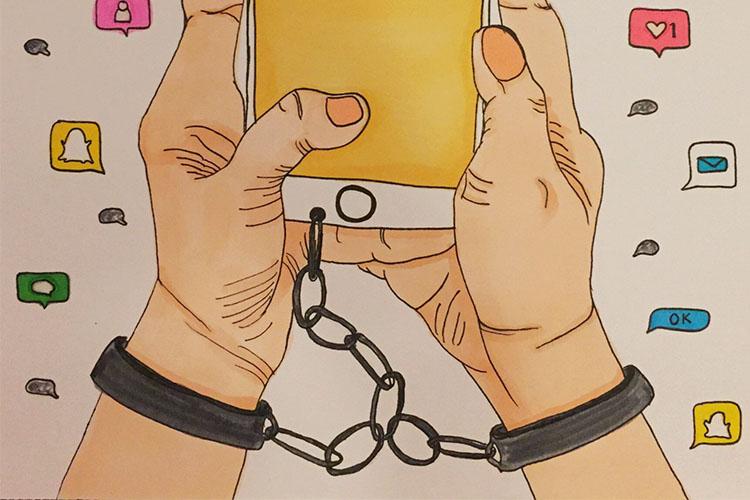

//PICTURED ABOVE: Students more financially secure are at a distinct advantage over those who do not have the same resources in the application process. Managing Editor Kate Woodhouse goes in depth about how financial status can affect college admissions.

“You are going to go to college,” English Department Chair Janet Bilhartz said to my freshman year English class as she informed us of our First Quarter grades. While this seemed like an insignificant comment at the time, I have come to realize the implications of what my teacher said. At Hockaday, college admission is guaranteed.

Because of Hockaday’s top tier teachers, administrators, college counselors and reputation, I do not have to worry about if I will go to college but rather where I will go to college. However, this is not the case for much of the United States population. Low-income and rural communities face numerous challenges to gain admission into colleges.

My relationship with higher education began almost immediately after I was born; some of my baby pictures even show me in a Baylor University onesie. Because both of my parents went to college, I am already at an advantage. While Dallas is not a traditional college town, many schools like Southern Methodist University, the University of Texas at Dallas and the University of North Texas permeate into Dallas culture.

Even though the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) has implemented initiatives to inform their students about college in elementary school, it is not the same thing as having a familial tie to a college. Rural students may have to travel many hours in order to arrive on a college campus, decreasing their likelihood of ever seeing a college. This exposure de cit only increases as children grow older. High school is a completely new ball game. As college quickly approaches, the “college gap” increasingly affects rural and low-income students in three main ways: educational quality, admissions testing and college counseling.

Students in urban and suburban schools in high-income areas receive a better education than those not afforded these opportunities. Hockaday and its peer institutions across the country can easily hire the most qualified teachers with appealing features such as the Child Development Center. They can also keep class sizes to a minimum. In fact, I have never been in a class of more than 20 students while at Hockaday, and my Spanish class now only has eight students. With enormous budgets for small classes, teachers can integrate technology and opportunities outside the classroom to stimulate learning.

However, rural and inner city schools cannot attract the same quality of teachers, as these institutions seem less appealing to top tier educators. Class sizes can soar as schools struggle to pay these teachers or do not have enough classrooms to t another class, causing less personalized lessons for students. Lack of facilities is one of the most common ways that the Texas Education Agency cites for class sizes being too big and is one of the exceptions that schools can claim to increase class sizes past the maximum amount. Currently, Texas does not impose a class size limit past fourth grade but does impose a maximum student-to-teacher ratio of 20:1. While this ratio may indicate the approximate number of students in a class, some teachers, like special education and gifted and talented teachers, either teach much smaller classes or teach students in a pull-out program. This increases the size of the typical classroom in Texas.

Since schools already struggle to pay their teachers and administrators, they have little money left in the budget for student enrichment opportunities. The subpar facilities in some schools also inhibit learning. Instead of paying attention in class, some students can be distracted when “the building leaks[s], the building is cold and damp[ and] parts of the building have classrooms with unbearable heat because the temperature cannot be regulated,” a student at South Oak Cliff High School said to Texas Monthly in 2015.

These students might also learn less information about college admissions tests, like the SAT and ACT, in the classroom, and therefore might not score as high. Many low income students also face other challenges to succeed on these tests. While both tests have fee waivers, these are not the only costs for the tests. Both the SAT and the ACT allow a calculator for at least part of the math section. Even though the tests advertise that all problems can be completed without a calculator, not having one puts students at a disadvantage over students that do. The cheapest Texas Instruments graphing calculators cost about $100, so some families cannot afford to buy one for their children.

Having money can also help students score better on the test. At Hockaday, some families shell out thousands of dollars to hire a private SAT or ACT tutor. Others attend classes at test prep companies like KD College Prep or the Princeton Review. Although Khan Academy has free SAT study resources, these are less personalized as the practice questions have to cater to the entire high school population and not towards one specific person.

Other students face difficulties reaching test centers in order to take the tests. Some rural high schools do not offer the SAT or ACT at every possible test date because it would not be pro table for the companies. If students wish to take the test on a date not offered in their community, they could have to drive hours to take the test in an unfamiliar environment, which also puts them at a disadvantage. With these disadvantages potentially lowering their scores, these students have a bigger disadvantage getting into college.

DISD high schools had a student to counselor ratio of 447:1 in the 2014-2015 school year, according to a Dallas Morning News article, and are only required to have one counselor per 500 students in middle and high school. Many public schools throughout the country have similar ratios.

Story by Kate Woodhouse

Illustration by Kemper Lowry