Corruption in the Texas juvenile justice system

How might Texans fight for change?

December 17, 2022

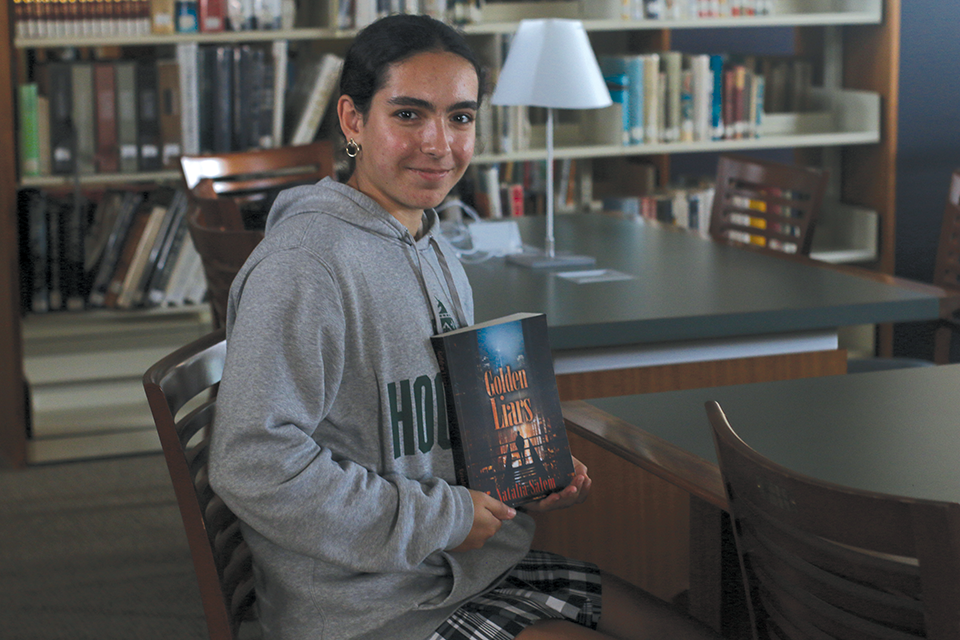

Though news outlets have recently shed light on criminal justice reforms, they have not highlighted the corrupt juvenile justice system nearly as much. On Nov. 10, Texas state lawmakers announced an agreement to modify the Juvenile Justice Department. But what brought about this agreement and what changes should be made to improve the broken juvenile justice system? This past November, Elizabeth Henneke, an advocate for juvenile justice, spoke to a Dallas group of around 30 individuals to spread her knowledge on necessary reform.

According to the State Office of Risk Management, the Texas Juvenile Justice Department “has had the highest injury frequency rate among all reporting entities over the last decade.” The Sunset Advisory Commission of the state legislature has reported a 71% turnover rate for juvenile correctional officers. The committee also reported a 35% increase in suicide assessments and a 19% increase in aggressive behaviors following lockdowns at juvenile facilities in the fall of 2021.

One organization working to reconstruct the failed system is Lone Star Justice Alliance. Founded by Henneke in 2017, Lone Star advocates for a justice system that uses appropriate responses for youth, combined with equitable and fair practices. Its goal is to provide real justice, combat juvenile reoffending and promote recovery in the juvenile justice system, ending the mistreatment of these victims.

Henneke, whose father was a juvenile correctional officer in Huntsville, was inspired to start her non-profit based on experiences during her own childhood. Every summer, at the jail where her father worked, she spent time with female inmates in the kitchen.

“I would hear their stories of how poverty and trauma had combined to lead them into the situations that had led to their convictions,” Henneke said. “I started to be really concerned that we were just cycling people in and out of those doors and not really doing anything to address the underlying condition.”

Striving to reform all aspects of the juvenile justice system, Henneke’s non-profit works in three program areas: Just Sentencing includes the representation of juveniles in court, the Reimagine Justice Institute creates policy change and Transformative Justice pilots alternative sentencing methods.

Henneke said the pandemic worsened conditions exponentially, with staffing shortages and a high turnover rate.

Because of a lack of staff to monitor the youth, detention centers have implemented lockdowns, during which the juveniles are forced to stay isolated in their cells. The juveniles can be locked in confinement for 23 hours per day, exacerbating behavioral issues, trauma, and mental illnesses among the inmates. Although TJJD’s website says “the juvenile correctional system emphasizes treatment and rehabilitation,” Henneke said the current conditions do not achieve this goal. Henneke also said the only people to blame for these harmful effects are the adults in charge of the system.

“There are increased concerns about the youth in these facilities, but they’re not the ones running them,” Henneke said. “Seventy-six percent of the kids in TJJD have serious mental illness, serious mental illness that requires intensive inpatient medical treatment. Those are the kids we’re locking up for 23 hours a day.”

In order to address these issues, Henneke said Texas should invest in mental health facilities, diverting children who need counseling, rather than prison, from entering the system. She said that alternative methods to incarceration like these would decrease the recidivism, or reoffending, rate. Henneke also believes that Texas should reevaluate juveniles’ culpability and whether some of their crimes actually warrant jail time. Among these are sex-trafficked adolescents escaping their abusers and those that received racially motivated sentences.

Henneke said Lone Star welcomes Hockaday students to get involved with the juvenile justice effort and join the organization, whether in local advocacy, persuading authorities or going to the Capitol to testify about policy proposals.

“It really is about harnessing the voices of youth,” Henneke said.