A world online

COVID-19 changed the way humans interact

January 28, 2023

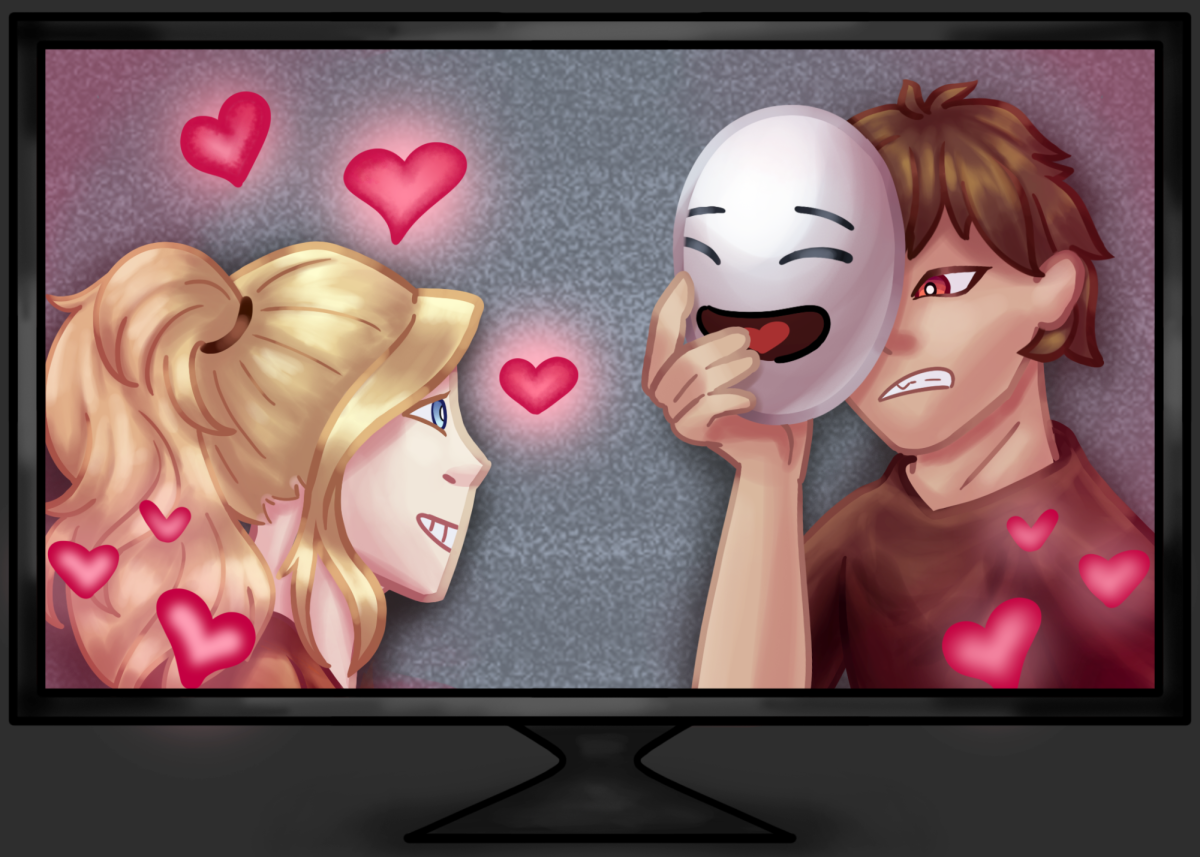

“Zoom: One platform to connect.” Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the word “zoom” was nothing more than a verb to describe a speedy action. Two years later, “to Zoom” has a new meaning: to connect without physical contact.

This virtual meeting space has revolutionized the way humans interact with each other on a day-to-day basis. People can now complete all daily actions from the comfort of their own homes: working, buying groceries, and even reconnecting with loved ones.

Although convenient, easy accessibility through Zoom has caused an increase in community seclusion and dip in mental health. Since the onset of the pandemic, anxiety and depression have increased by 25 percent worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. Social isolation has been the biggest stress factor on mental health.

Virtual World

With the move to this “virtual world,” new human behaviors and patterns have emerged that reflect the changing society. Dr. Karen D. Lupo, professor of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University, said lock-downs during the pPandemic changed the way everyone lived.

“Social isolation is unnatural for social creatures such as humans,” Lupo said. “People became more aware of those around them and avoided even simple contact.”

While Zoom and other methods of distance communication made meetings and teaching possible, Lupo said it became much more difficult to interact on a natural level. Conversations became more structured and less spontaneous.

Although this online pattern had been present before the pandemic, Lupo said she expects it to be accelerated as a result.

Despite the dips in mental health, accommodations offered during times of social distancing have actually made day-to-day activities much easier.

“Contactless checkout is something that will be with us forever,” Lupo said. “Although food delivery services have been around for a long time, people got used to these services during the pandemic.”

Anthropologists predict that typical ways of greeting people, such as shaking hands or hugging, will never return fully, Lupo said. While this may seem insignificant, some cultures are forever changed – for instance, the Italian and French who used hugs and kisses as a way of salutation.

Caroline B. Brettell, University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University, said COVID-19 allowed society to discover and solidify the potential of online interactions. Some people connected with others they had lost connection with, meeting in a more intimate and private space on Zzoom rather than on social media.

“It has reinforced old friendships, and families that are scattered have been brought closer together by taking advantage of these online tools,” Brettell said. “But, again, we need to learn to strike a balance between the way we used to interact and these new opportunities – each has its place.”

Brettell and Lupo said the post-pandemic world has been reminiscent of life after the Bubonic Plague in 1352. The number of people who died is comparative to that of COVID-19 deaths. Europe was left in a short supply when it came to labor, similar to how the United States now experiences labor shortages due to the number of work-from-home jobs.

“Technology keeps on changing the way we behave,” Brettell said. “Think of inventions like television, streaming, the telephone, and motor car and air travel – all these huge leaps in technology have fundamentally shifted human behavior.”

Social Skills/Communication

Ring around the Rosie replaced with squirts of hand-sanitizer, alphabet letters articulated through masks and playground games socially distanced, the pandemic lifestyle prevented young students from experiencing the typical version of school. With a decrease in in-person interactions, studies have shown children’s social and communication skills have been affected.

In a study commissioned by the STEAM brand Osmo and conducted by OnePoll, two in three parents felt their children have become more socially awkward. Eighty-one percent of the parents supported the idea of schools adding activities to develop social skills in this post-pandemic world. According to JAMA Pediatrics in November of this year, screen time has increased by 52%, or around 84 minutes, since the beginning of COVID-19.

COVID’s disruption to routines prevented formative childhood experiences in the development of social behaviors. Kelly Smith, a registered integrative behavioral nurse, said in a Forbes article that school closures, lagging educational progress, increased screen time and isolation among family members are all reasons for this drop in social skills among young children.

Dr. Matthew Housson is the founder of the Housson Center, which provides psychological and education services in Dallas. Like Smith, he has seen social skill problems emerge among children in the wake of the pandemic. Yet Housson has also identified that these decreased social skills are a result from the lack of enlightening, in-person connections during COVID.

“I think connection allows us to listen, hear another person’s perspective, have empathy for their perspective, even though we may not agree,” Housson said. “I think we’re seeing a lot of kids who have differences in their social communication skills, just the ability to interpret body language, the ability to display prosocial behavior.”

Housson said the virtuality resulting from the pandemic has allowed for ease in communication, but ultimately, these types of connections are not as fulfilling.

“We know it’s easier to connect,” Housson said. “We go from social media to video game playing, Snapchat, BeReal, all the different techniques that kids use to connect. But there’s a loss of opportunity to do other things. So people aren’t reading books, people aren’t exercising as much. People aren’t engaging with each other in a more meaningful and typical way.”

Overall mental Health Effects

Housson described how the pandemic opened eyes to the effects of virtual relationships on mental health.

“I think everyone assumes now there is a mental health crisis,” Housson said. It’s not the mental health crisis in question, it’s how long will it go on?”

As with the variants of COVID, there have been a variety of reasons mental health has suffered. Housson links this overall drop in mental health to the same cause as decreased social skills: changes in communication.

“I think what happened during the pandemic is, there was just a loss of connection,” Housson said. “Even though people were connected through social media, there weren’t hubs of connection, and so I think for a lot of reasons people got very disconnected from each other and out of routines. We’re still seeing a significant lag and kind of ripple effect that’s impacting mental health.”

Housson also discussed a podcast he recorded with pediatrician Dr. Early Denison and pastor Dr. Andy Stoker. They analyzed “Future Tense,” by psychologist Dr. Tracy Dennis-Twiary. She raised a term that caught the attention of Housson: “anti-fragile.”

Housson said Dennis-Twiary highlighted the fragility of glass, and how it’s impossible to put it back together if broken. Contrarily, mental health, muscles and immune systems may break, but can be put back together. The term “anti-fragile” identifies this innate human strength. Housson believes that people can confront stress and develop their anti-fragility through in person connection, rather than avoiding their anxiety by staying home.

“What we’ve learned is when people go out and they reconnect, and they engage, and they identify painful emotions, they name their emotions to tame their emotions,” Housson said. “They become anti-fragile, which means they become stronger from a mental health perspective. We’ve had the tidal wave with ripple effects, but I think the way that we come back is by strengthening our immune systems, our mental immune systems.”