You are never alone

Upper School fosters a community that educates and supports students as they navigate relationships, consent, self-defense and sexual assault.

May 25, 2023

Content warning: The following articles contain material covering sexual assault that may trigger some individuals.

How the school supports students

Dr. Tiffani Kocsis wants to give students what she didn’t have at their age.

Kocsis, assistant head of Upper School, is interested in building trusting relationships with students to help them navigate high school. Growing up, Koscis said she had limited resources to help her learn about health-related topics.

While Kocsis said Hockaday could start conversations regarding sexual assault earlier and have them more frequently, she says the school does a good job of educating the students.

“I do believe that we do what we’re able to,” Kocsis said. “Our health program discusses assault and ways to protect yourself, and our self-defense class is top-notch.”

According to Kocsis, if a student reports to a faculty member that they have been sexually assaulted, whomever is told must notify Child Protective Services and Head of Upper School Lisa Culbertson or Head of School Laura Leathers, since faculty members are mandated reporters.

Upper School Counselor Ellen Kaney-Francis specializes in recovery from traumatic interpersonal violence experiences. She said the effects of trauma are varied and may be endured throughout life, and everyone deserves the opportunity to process their experiences in meaningful, affirming and healing ways.

“True consent in a relationship, and, specifically, in sexual intimacy, is freely given — no guilting or coercion of any kind — enthusiastic, and must be ongoing,” Kaney-Francis said.

“Ongoing consent” means regularly ensuring that your partner is in agreement and comfortable with what’s happening at all times,” Kaney-Francis said.

Kaney-Francis offers support to victims through validation and education, which she said are simple yet powerful interventions.

Believing survivors and their experiences and explicitly saying, “I believe you,” are essential to demonstrating genuine, non-judgmental support. Talking about the various forms of sexual abuse, which can include rape, as well as the components of consent and self-care or medical care options is what Kaney-Francis does to educate sexual assault survivors.

Kaney-Francis said people do not have to be ready to call what happened to them “rape” or “sexual assault” to seek help and receive care. For survivors, it is important to find a place or person that will accept them at whatever stage of shock, grief or healing they are in.

While it is her area of expertise, if a student were to disclose an instance of sexual assault, Kaney-Francis would not engage in trauma therapy with them in her office.

“I would remain a safe person on campus should you need a quiet space to take a break or talk,” Kaney-Francis said.

Kaney-Francis said that for survivors, school is the place to be a student, and they deserve to have some ‘normalcy’ on campus, if at all possible. She recommends that they utilize outside resources to specifically address the traumatic event.

Ideally, school counselors are viewed as safe people to talk to about any significant events, including those that might have nothing to do with campus life. Students often worry that it is “too much” to share with a counselor, but Kaney-Francis said counselors want to hear whatever students need to get off their chests.

According to Kaney-Francis, for a sexual assault survivor, the counselors can help alleviate the pressure of schoolwork if they deem it best for the student’s stage of healing.

“It can be nearly impossible to concentrate on or care about assignments when you’re trying to make sense of what happened to you,” Kaney-Francis said.

Students should know that any faculty or staff on campus will provide compassion and not blame when speaking about sexual assault.

Kaney- Francis is thankful that health classes explore the dynamics of healthy and unhealthy relationships and sexual abuse and assault. “We have to discuss consent. I’m so glad Hockaday creates space for this,” she said.

Consent and sexual assault education

Upper School Health and Physical Education teacher Adaku Ebeniro is passionate about the curriculum’s lifelong lessons and argues Health is one of the most important classes a student will take.

“The concepts taught in health classes stay with a student for a lifetime and anything that will allow people to look inwardly and learn to navigate the highs and lows of life is a huge priority,” Ebeniro said.

To Ebeniro, consent means having a clear idea of your own and others’ boundaries and knowing when these boundaries are being crossed. She said it depends on confidence in who you are and not worrying about how people react to the boundaries you set.

Ebeniro said consent is taught at developmentally appropriate levels at Hockaday. It is first introduced in Lower School with an emphasis on boundary-setting in terms of physical space and verbal conversation. In Middle School, conversations of reproductive and sexual health begin, along with Texas’ laws regarding consent. Sophomore year, educators teach that consent is an active process; this means someone can change their mind at any time if they give consent and end up not feeling comfortable with whatever the activity is.

While Ebeniro believes discussing consent promotes conversations about it outside of class, she wishes the community had more opportunities to do so.

“A lot of these concepts can’t be limited to one unit in a health class – it should be pervasive throughout all subjects, curricula and grade levels,” Ebeniro said.

When a student confided in Ebeniro about her sexual assault story, the first thing she did was make sure the parents and a counselor knew.

“Her parents were aware; she was in therapy, and I was happy she got the help she needed,” Ebeniro said.

Ebeniro said teaching about consent, sexual assault and victim blaming gets difficult. As a big proponent of therapy, counseling and any other healthy coping mechanisms, Ebeniro finds comfort in helping by making herself an available liaison and resource for students. However, she makes sure to keep a healthy distance from it to protect her own mental health.

“I try not to take too much on because I also have to release it as well,” said Ebeniro.

Upper School Self-Defense Instructor Jessica Jasper is another resource for students. She specializes in martial arts and protective services and teaches self-defense classes for Upper School students.

She teaches students how to accurately assess risks and introduces the five principles of defense to seniors: avoid being an easy target, trust your intuition, be aware of your situation, predict violence and defend yourself verbally.

Two additional topics students learn in the course are active shooter survival and vehicle safety. The bulk of the course includes learning effective martial arts techniques from jiu-jitsu and Muay Thai.

While the semester course is taught to seniors, Jasper teaches a unit of self-defense to sophomores, and she believes younger students would benefit immensely from the course.

“I think this course drastically lowers the likelihood of being targeted by abusers in the first place, assuming that the student has applied herself and understood the concepts covered,” Jasper said.

Jasper said students learn how to be a “hard target” by identifying what makes someone an easy target for abusers so, ideally, they never have to use their physical defense skills in the first place. They also learn how to identify violence or other types of abuse, allowing them to make a plan to avoid it.

“A lot of the students finish up the course with some really amazing martial arts skills – a few of them kick harder than I do,” Jasper said. “The goal, however, is to never have to use those skills except for fun.”

Student perspectives

Senior Meera Malhotra has completed all of Hockaday’s health curriculum since she came to the school in fifth grade. Malhotra remembers learning about period cramps and drug use in Middle School, but doesn’t remember much of the sophomore curriculum, as it was during COVID. In the self-defense course, Malhotra has learned how to defend herself in case of an attack and how to appropriately get out of those situations.

“I have used my knowledge from these classes to help navigate my outside relationships with others,” Malhotra said.

Junior Varsity Lacrosse player Caroline Warlick has participated in the OneLove Foundation with her team to spread awareness about abusive relationships.

Through workshops, Warlick has learned the importance of communication in relationships and how that can affect the people she interacts with. In their workshops, Warlick and the lacrosse team learned to identify the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships.

“I think it is so important to understand a relationship is never going to be perfect, but we should all have the ability to recognize if a relationship doesn’t feel like love,” Warlick said.

After the OneLove lacrosse game, Warlick hopes people reflected on the relationships they have and urges them to look at OneLove’s website, which provides resources for those in domestic violence situations.

Conversation with a survivor

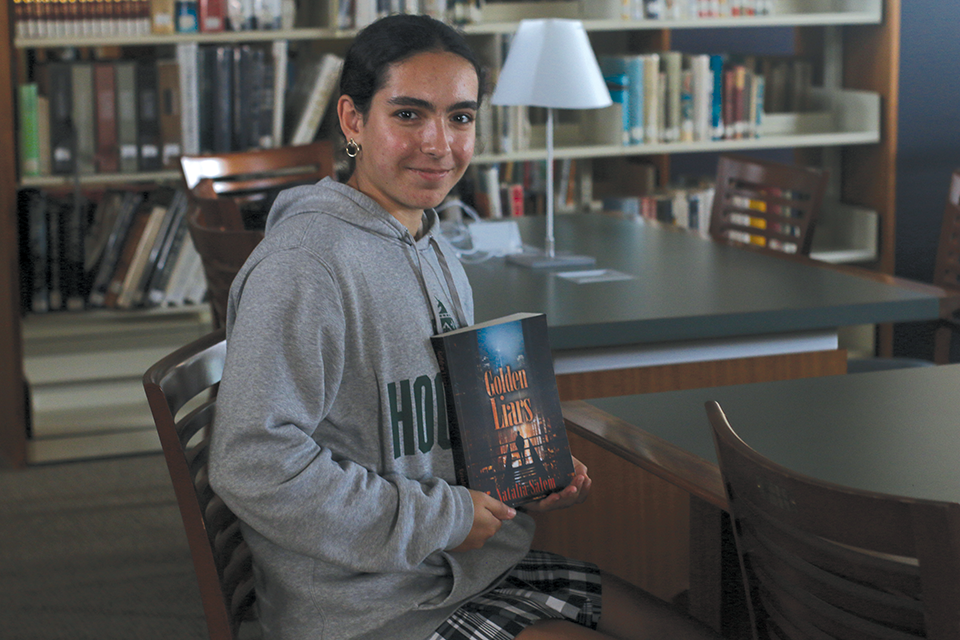

The student in this article, who asked to remain anonymous, survived a sexual assault. She has shared her story to help other survivors know they are not alone and to spread awareness that this could happen to anyone.

Q: Where would you like to start? Would you tell me what you are able to remember about your experience?

A: I was at a party and I drank a little bit during it. I didn’t know anyone else there and a guy came up to me and put his arm around me. He asked me to come to his room and he pushed me onto the bed. Then it happened.

Q: Did you report the assault? And if so, were you scared to report him?

A: I was very scared to tell my parents because I thought they were going to kill me. When my dad found out the assaulter was 19, he wanted to press charges but I didn’t.

Q: Who or what helped you navigate and cope with this difficult experience?

A: Right after it happened, I started over-sexualizing myself and I found that this is pretty common among other survivors. I also turned to partying a lot. It didn’t affect me in the way that you think it would because I wasn’t scared of men — I was more drawn to them, and often found myself doing more hookups and not anything deeper when I really wanted a relationship. My friends and talking to my therapist also helped me.

Q: Do you think consent from a girl’s perspective differs from a guy’s? In what ways?

A: Definitely. Often times I hear stories and the girl’s and the guy’s perspectives are very different. The girls say, “I didn’t want this to happen,” while the guys say, “She wanted it and she was the one that started it.” There is a thin line between consent and sexual assault and it depends on their state of mind. Nowadays you really have to ask the questions and make sure everyone’s comfortable.

Q: Where do you think this difference in perspective comes from?

A: I think it is based on the way people are taught and raised. Although the conversations can be uncomfortable, they are necessary, and without them, guys would think they can do whatever they want with girls. Parents and schools should teach both guys and girls about consent so they can learn what to do in situations like mine.

Q: Do you feel like the health curriculum at Hockaday helped you?

A: The class taught me a lot, like different types of protection and ways to handle

certain situations. My teacher offered real-life perspectives, which were super helpful.

Q: Can you give me examples of implied consent and what that means to you?

A: Consent comes in many forms, whether it’s straight-up asking or checking in while doing stuff. If you are comfortable, you can sit down and discuss what your boundaries are, what you want to do, and what you are not comfortable with prior to the experience. Consent means different things to different people so setting your boundaries with your partner is very important. Sadly, there will be people who don’t care about your boundaries so finding a trusted adult to talk to about boundary setting is fundamental.

Q: To you, what is victim blaming? Would you say you felt victim blamed after your experience?

A: The way my parents reacted was really hard because they are supposed to be the ones you trust.(One parent had a stronger reaction than the other.) I also fought with myself internally because I would compare myself to others who had it worse and think my experience wasn’t as bad. Society will also blame survivors with comments like, “You shouldn’t have dressed or acted this way.” It’s also hard as a teenager because you are still trying to figure out who you are and there’s a lot of pressure.

Q: What do you want to say to young girls who have experienced this?

A: Find people you trust and who really care about you because they will be the ones that stick by your side no matter what. Remember your worth and don’t let people define it. Sexual assault is never your fault.