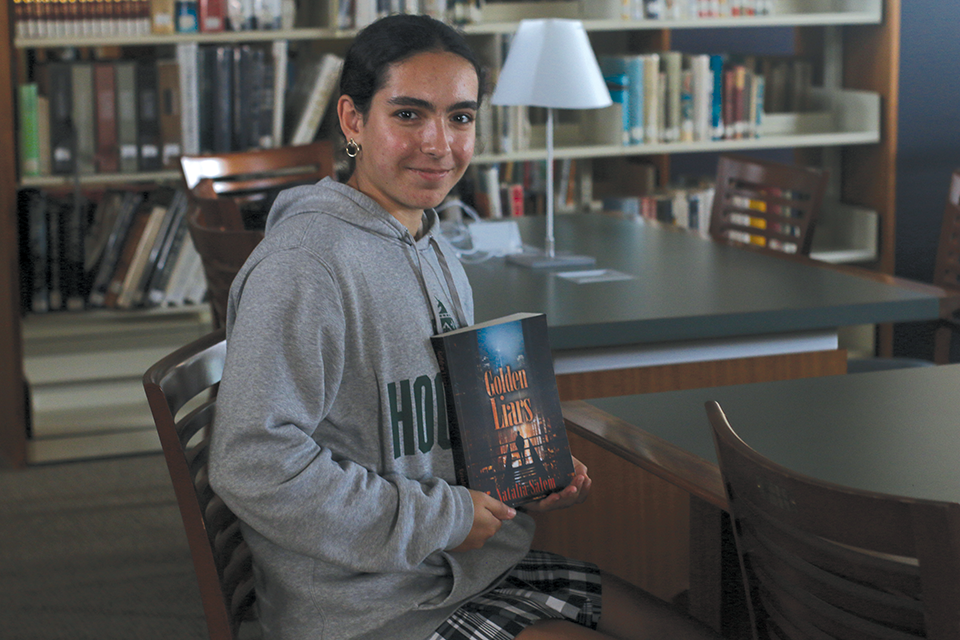

Teachers and students weigh in on the curving culture at Hockaday

When most junior girls looked at their raw percentages on the Precalculus exam this past April, they panicked. Their percentage, a score that would ultimately affect their final grade for the year, was much lower than expected. It’s a situation that any student can relate to.

Come spring, the tests become cumulative, the breadth of material increases, the stakes get higher and the anxiety grows. But with a little bump from a curve, most students’ end-of-the-year worries can be quelled.

“I like curving because it boosts your confidence level about how well you know the material,” senior Kaitlin said. “It means you weren’t the only one who thought the test was difficult.”

Though students and teachers may call it curving, traditionally, curving implies using a bell curve, where most of the scores will rest in the median range with a few extremes on each side.

Upper School math teacher Grabow said that “typically, you’ll have the mean around an 80 and then very few A’s and F’s, but that’s not what most teachers do here at all.”

In many cases, the lower the grade, the higher the curve will be. This technique raised the scores of many of the Precalculus exams. It benefits the students with lower grades while giving those with the higher scores less of a curve, therefore messing with the bell shape.

Most curving methods used at Hockaday, such as moving one student’s score to 100 percent and adding the same number points to every single student, do not benefit everyone. In that situation, if the highest grade were a 98 percent, those on the bottom would only add two percentage points to their raw scores.

“I think it’s just being generous and I think that a bell curve does work better,” junior Payton said. “It’s not necessary for the people at the top to get as many points as those below.”

In the most democratic of the methods, an equal number of points can be added to each test and every student receives the same benefit.

“The problem…is it’s always going to benefit the students that have the higher grade and really your curve is not really geared towards those with a 80 or a 90,” Upper School Spanish teacher Mariana Mariel said. “You want to help those at 50 or 60. So giving the same amount of points makes it equal.”

However, this does not encourage students to learn from their mistakes.

“It’s not like if everyone does poorly, they automatically get points,” Grabow said in reference to her curving approach. “It is more based on the difficulty of the test than how the group of students does.”

When the students do poorly on a test not technically difficult in the opinion of the teacher, there are certain situations that do not call for using a curve.

“If the test is straightforward or they have seen the questions before or they don’t have to figure out a new idea in a timed assessment, their grade might be a straight percentage,” Grabow said.

However, the policy can change based on each teacher or the rigor of the class. Grabow said that the school does not suggest one standard way to curve.

“When I came to Hockaday, they really said that you, as a teacher, have freedom within your own classroom,” Grabow said.

That means that girls will learn the same material but often receive different results not only due to the difference in teacher but also the differences in their curving policies.

“[Upper School math teacher Jessica] Chu and I might share a question, and there might be some similarities, but you can have different tests even when you’re in the same class just based off of your teacher,” Grabow said.

Upper School history teacher Tracy Walder does not consider giving students back points for difficult questions as “curving, but rather as being a thorough teacher.” To her, if the majority of students miss a question, that reflects more on the teacher’s lesson than the student’s knowledge.

Walder only curves cumulative assessments, such as the March exam and the AP multiple choice practices for U.S. History, which she gives out towards the end of year in preparation for the AP examination in May.

She takes the cumulative nature into account and does not expect “students to get a 100 on it,” reasoning that because the College Board grades on a curve, major grades in the class should be graded on one as well.

Grabow agreed and treats AP related material differently.

“In my AP classes, we do a lot of AP questions all year long, including on quizzes and tests. Those are designed to be more challenging,” Grabow said. “You are not supposed to get a 90 percent or an A.”

That remains true for other classes as well. The material is not designed for students to be able to score extremely high on. When this occurs, partial credit becomes crucial and grading students relative to their classmates becomes more common, like in the AP Biology class.

If you get a certain percentage, there is an AP equivalent. Every single test we take is curved to the AP,” said Payton, an AP Biology student. “You’ll get a number and then you’ll also get a letter grade.”

However, not all classes can allow partial credit when the material becomes more challenging.

“It is difficult because events in history either happened or they didn’t,” Walder said, remarking on the idea of partial credit as a form of curve or bonus points.

Particular topics in the science or math classes may be especially difficult for certain students. This can be reflected in the comparison between test scores of different units and quarters. While the Puritans and the colonial era may trip some students up, the grades do not drop or rise dramatically between units.

“Students do have more trouble with particular eras, but it’s never enough to give a curve,” Walder said.

Mariel does not use curving in her class but has other methods intended to help students out.

“I don’t actually believe in curving. I do give extra credit for certain activities that are beneficial for students, like maybe going to a play where you are watching something in Spanish,” Mariel said.

Teachers like Mariel take every chance to provide more learning experiences.

“Every opportunity that we have where the students can be immersed in the language then we give extra credit for that,” Mariel said.

Grabow also suggested giving more chances for improvement, but in the form of a quiz or in-class activity.

“When you need to give a grade boost, you just give an easier assessment,” she said. “That way you aren’t technically curving it.”

All of these different techniques stem from the same argument that students may not ever learn the material if given a curve.

“If you’re given points back, you’re not really learning it,” sophomore Cameron said.

As Mariel said, there is no way to prove when students have learned the material unless she “retests and sees improvements later on.”

Mariel argued that curving can be unnecessary when students can bring up their grades themselves based on their own knowledge, a much more rewarding solution for both teachers and their students.

“I always try to not just give but allow the students to have the opportunity to bring up their grade with what they can do and how they have improved on this particular material,” Mariel said.

But the need for curving will never go away as the material gets more and more difficult and teachers want girls to do well.

“I think we don’t want girls to feel inadequate with the material,” Mariel said. “I hate to think that it’s because of that because then we’re not giving you girls the right education or the right service.”

-Katie