Fifty years ago, you would never hear the acronym “STEAM” in Hockaday’s hallways.

“When I was at Hockaday, I don’t remember career ever being addressed,” Suzi Greenman ‘61 said. “I always pictured myself playing a strong, supporting role for my husband, who I imagined would be a corporate executive, and playing an active role as a community volunteer.”

Greenman graduated 53 years ago and Hockaday’s vision has changed.

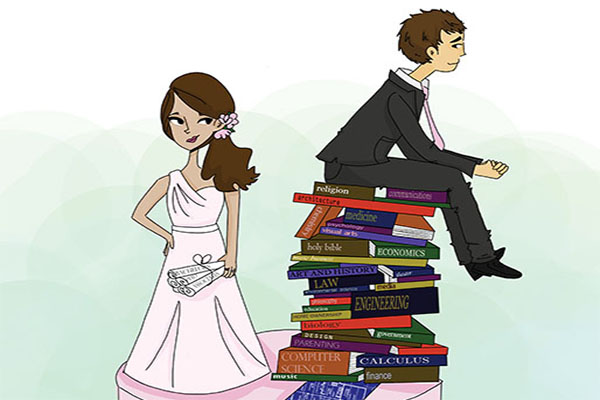

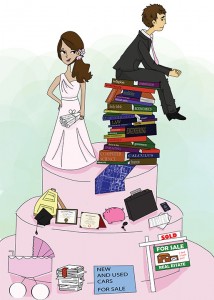

Eighty-eight percent of surveyed Hockaday girls want to get married. Eighty percent want to have children at some

point in their lives, and 42 percent consider religion to be an important part of their lives. Despite Hockaday’s progressive, forward thinking environment, some members of the community still hold on to tradition, even as the world around them does not.

Evolution is necessary in order to move forward, but is it possible to evolve while still staying true to our customs and beliefs?

Something Old, Something New

The contrast to the 88 percent of current Hockaday girls who want to get married, 100 percent of 1958 to 2011 alumnae surveyed thought that while at Hockaday, they might or would want to get married eventually. Ninety-one percent of these alumnae ultimately did or would still like to.

“Most of us wanted to go to college out of state. Very few envisioned a career other than teaching or something similar,” Linda McFarland ‘61 said. “Most assumed we would marry and have a family.”

However, beginning in the 1980s, alumnae started to see a shift in Hockaday’s attitude towards tradition.

“Hockaday certainly stressed career,” Elly Sachs Holder ‘82 said. “But, it provided the opportunities to learn and excel in whatever areas interested you, while still saying it was ok to aspire to the traditional roles of women like motherhood.”

By the late 1980s, the talk of traditional roles, however, had become almost obsolete.

“I don’t remember motherhood or marriage ever being discussed,” Meg Temple ‘88 said. “However, I remember a lot of discussion about career choices.”

Hockaday girls, consistent with the generational trend, do want to get married, despite a growing culture of many women not having long-term relationships.

The Economist reported in January 2013 that 51 percent of American adults are married, in contrast to 72 percent in 1970.

Sheri Kunovich, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology at Southern Methodist University and recipient of Margareta Deschner Teaching Award in Women and Gender Studies, said that women are less interested in marriage than ever before for three reasons.

“Society’s traditions have changed to allow greater freedom to pursue physical romantic relationships outside of marriage without stigma, greater economic independence and a culture that increasingly accepts adults, specifically women, who choose not to have children,” she said.

Despite these statistics, tradition still has a place at Hockaday. This is not a surprise. Female college graduates are now at least two times as likely to get married than non-college educated women, according to The New York Times.

“I want to get married because it’s a tradition in my culture and my family,” an anonymous sophomore said.

In the face of progressivism, girls who still want to hold onto tradition are merely adapting. Rather than getting married right out of college, women are waiting until their careers are established before entering a committed relationship.

Family’s Fading Importance

The American tradition is to start a family. Only four percent of Americans don’t want to have children, according to a 2013 Gallup poll, an American researching and polling company.

Alumnae adhered to this traditional practice, with 91 percent saying that while they were students, they saw children in their future.

Some current Hockaday girls believe in progressivism in regards to family, with 20 percent saying that they do not want to have children. However, these percentages are not consistent with the national data. A Pew Research study reported in 2011 that the Millennials, children born between 1980 and 2000, value being a good parent over having a successful marriage and are the first generation to have this belief.

As a general consensus, Hockaday girls equally value their future husbands and their children. The more difficult decision is between their families or their careers.

According to Gallup, many who choose not to start a family do so in order to focus on their careers. Hockaday girls assert the contrary. “You can have kids and a career, it’s not a myth [you can have both],” junior Bella Manganello said.

However, some women disagree. An anonymous junior thinks the opposite.

“I plan on waiting to have kids until I feel like I have reached my work goals in life, yet once I do have kids, I want to be 100 percent focused on their lives. My priorities will come second,” she said.

However, finding a balance between family and career is important to many Hockaday girls. Thirty-seven percent of girls surveyed answered that they would “take a few years off from their careers to raise their families and eventually return to the workforce.” Ninety-six percent of alumnae surveyed did return to the workforce after having children. However, many of them did not return to the workforce for over a decade.

In her book “Lean In,” Sheryl Sandberg cited the statistic that 43 percent of highly-qualified women with children are either leaving their careers or ‘off-ramping’ for a period of time. However, 74 percent of these women, Sandberg wrote, will “rejoin the workforce in any capacity,” and 40 percent will return to full time jobs.

Many alumnae are included in Sandberg’s 74 percent. “I pursued a career in marketing after college, but 10 years later became a stay-at-home mom,” an anonymous alumna said. “After being a full-time parent for 5 years, I returned to work full-time. Because of Hockaday, I was taught that I could have it all.”

Faith on Whose Terms and at What Cost

Freshman Emily Fuller discovered her love for Christianity at a Hockaday Young Life meeting she attended with her friends last year. There, she learned about the religion and grew more and more curious.

“Before, I had this idea in my mind of Christians being homophobic, strict rule-followers,” Fuller said. “Now, I know what it actually means to walk with Christ. Christianity is about love for Christ and spreading his glory.”

An anonymous sophomore echoed Fuller’s anchor in religion. “Religion is probably the only thing keeping me alive at this point,” she said. “It’s the idea that somewhere out there is someone or something that loves me unconditionally, that I have a purpose in life. I don’t care if I’m right or wrong; I just need to have something to lean on when everything else fails.”

Religion might not be as important to some Hockaday girls as it is for others. In a survey conducted by The Fourcast, more girls answered that religion was “sort of” or “not” important to them than those who said it was. This represents a much more progressive religious trend prevalent throughout the nation.

Devotion is not the sole requirement for being able to identify with a faith. Sophomore Melanie Kerber, for example, identifies as Jewish, despite some questioning how religious she really is.

“Both inside and outside of Hockaday, I feel like people try to police my Jewish identity and tell me that I’m not ‘Jewish enough,’” she said. “Just because I don’t keep kosher all the time and don’t look ‘classically Jewish’ doesn’t mean I’m any less of one.”

According to the National Study on Youth and Religion, almost 40 percent of adolescents “drop out” of their respective religion and another 38 percent eventually leave religion entirely later in life. The study contributes this statistic to the fact that oftentimes, teenagers go to services at their parents’ insistence rather than their own independent desire. This assumption can be seen at Hockaday as well, as 35 percent of Hockaday girls reported that religion is more important to their parents than to themselves.

Junior Caroline McGeoch, one of the leaders of Hockaday’s Bible Study Club, has also noticed girls at Hockaday moving away from religion.

“I think many girls get detached or too busy,” McGeoch said. “They find that religion lacks relevance and move away from it.”

Although sophomore Sabah Shams sees herself as culturally Muslim and agnostic, someone who claims neither belief or disbelief in a higher power, she does not identify with much of the tradition surrounding religion.

“I still attend services to be part of the community and to appease my parents,” Shams said. “But I don’t feel the importance of getting to the monotony of traditional rituals that don’t have any personal meaning behind them.”

Shams, among other girls, chooses to look at religion in a more progressive way, if at all. According to The Fourcast survey, 58 percent of girls feel uncomfortable discussing religion with their peers.

Junior Juliette Turner, another leader of Hockaday’s Bible Study Club, attributes this discomfort with fear of being incorrectly labeled.

“Religious expression has become perceived to be discriminatory towards other religions,” Turner said. “I don’t feel able to express my religious views without offending someone else or getting labeled as a religious freak.”

This isn’t just confined to Hockaday. Ted A. Campbell, Ph.D., associate professor of Church History at Southern Methodist University, says it is a national attitude.

“It’s ironic that in an a time when we encourage people to speak more forthrightly about their identities in areas like culture or sexual orientation, U.S. culture has begun to discourage people from speaking forthrightly about their religious identifications, because of the negative opinions and actions the press has shown certain religious groups as having,” he said.

Do these negative attitudes signal a decline in people being traditional?

Hockaday girls have not become less “traditional,” but rather less open to speak about their traditions. This silent majority is faced with a choice: either stay silent to avoid confrontation or risk being challenged to adapt to a more modern ideology.

“If I use a traditional viewpoint to justify my opinion, people no longer count it as a ‘relevant’ reason.” an anonymous junior said. “I’d rather not risk standing out, but I don’t want to change what I believe just because I’m told it’s no longer current.

Kate Clement, A&E Editor